Where did the last negotiation round for a High Seas Treaty take us?

By Arne Langlet, Ina Tessnow-von Wysocki and Alice Vadrot

After two weeks of negotiations, the planned-to-be final intergovernmental conference (IGC) for a new instrument to govern marine biodiversity beyond national jurisdiction did not end with a treaty but with the decision to reconvene in August 2022 for a fifth IGC. In our MARIPOLDATA Blog on the first negotiation week, we analyzed state preferences regarding the package elements Capacity-building and Transfer of Marine Technology (CBTMT), Marine Genetic Resources (MGRs) and Area-based management Tools (ABMTs), including Marine Protected Areas (MPAs). This blog summarizes outcomes of the second week of negotiations.

Where is the often cited “common BBNJ canoe” going?

Recap of second week:

Overall discussions during IGC 4 were less polarized and general flexibility made the negotiations progress faster in comparison with previous sessions. There seems to be agreement that the Conference of the Parties (COP) – the future decision-making body of the new instrument, should be empowered to establish Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) in the High Seas and that a dedicated secretariat would be the best option to implement the future Treaty. Although governments did not have time to discuss all text passages and intersessional work will be highly needed, IGC 4 gives hope that states are committed enough to finalize the treaty text at the next and final negotiation round in August 2022.

After a brief recap by the facilitators on the topics discussed in the first week, the second week started with Crosscutting issues (CCI) from Monday until Wednesday morning. Wednesday and Thursday were used to negotiate the EIA chapter. On Thursday afternoon the substantive negotiations concluded with discussions on the use of terms under Crosscutting issues. On Friday – the last day of the conference – delegates and facilitators took stock of the progress made, decided on a way forward and delivered closing statements expressing their committment to finalizing the BBNJ Treaty.

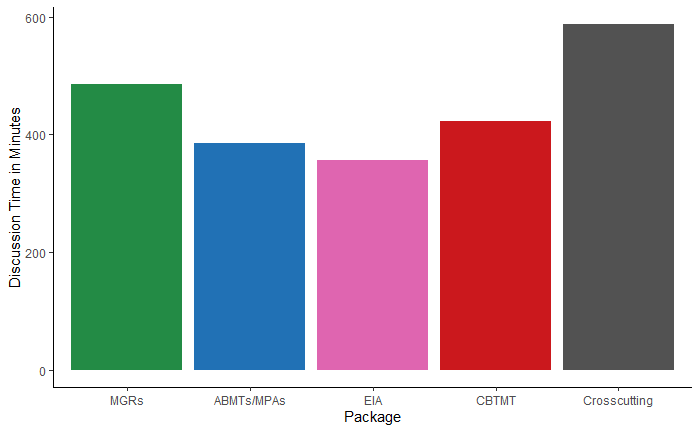

When looking at the netto talking time for each of the package items, we see that Crosscutting Issues took up most of the time, whereas the EIA Chapter was the least discussed during the whole two weeks – although the EIA Chapter is the longest in terms of text and individual provisions.

Graph 1 – speaking time of state delegates per package

Crosscutting Issues:

Under the crosscutting issues chapter the negotiations addressed Article 48 (Conference of the Parties – COP), 49 (Scientific and Technical Body – STB), 50 (Secretariat), 51 (Clearing-House Mechanism – CHM), 52 (Funding), 53 (Implementation and Compliance), and 54 and 55 (Settlement of Disputes). On Wednesday and Thursday, the discussions moved to the EIA Chapter before turning back to Crosscutting Issues on Thursday afternoon to discuss remaining issues under the Settlement of Disputes Provisions and Chapter 1 on the Use of Terms.

Rapidly, consensus on some general issues could be found. For instance there was broad support to establish a COP as the main decision-making body of the treaty. There was also overall support for review and assessment by the COP. While there was general agreement by delegations to make reports and decisions of the COP publicly available, some delegations stated that it would not be necessary to mention it in the text, as ”this is not a secret meeting”. Further, there was agreement that the COP should adopt its rules of procedure and may establish subsidiary bodies if deemed necessary for the implementation of the Treaty, but parties disagreed on the need of a list of subsidiary bodies to be mentioned in the text, which would guarantee their timely establishment independently of COP decisions in the future.

On the modalities (Art. 48. 3) of decision-making in the COP, disagreement was voiced. While some states insisted on consensus to decide on any matters – which would give any party a veto right – many other delegates pointed to the need to have the possibility of majority voting in case COP decisions get blocked, making the COP unable to act. The possibility of opt-out provisions were discussed, mainly in regards to ABMTs, including MPAs to achieve a higher number of signatories to the agreement, but was cautioned against by others, questioning the overall effectiveness of conservation measures with such an option to “pick-and-choose”.

The future Scientific and Ttechnical Body (STB)

While there seems to be no question that science and knowledge is needed to inform global policy-making and to effectively support the implementation of the new BBNJ agreement, detailed characteristics of how such a body should look like, what its powers and functions ought to be and which experts would need to be represented – needless to say how to select them – has gotten very little attention throughout the BBNJ process. Informal discussions during the intersessional period touched on this topic by asking very specific questions on how many experts the delegations envisage for such a body, and what this body should be tasked with. In the actual negotiations, however, this important topic has only received little time on the agenda as one of many institutional arrangements to be discussed.

Overall, delegations largely agreed that the STB would have an advisory function, operating under guidance of the COP (Art. 49. 4). While it should focus on the scientific and technical (and technological) advice, the COP can further elaborate on its functions. In this regard, the intersessional period will be key to discuss these details, if one wants to avoid to leave essential elements to be delayed to later COP decisions.The MARIPOLDATA Team will contribute to this discussion by looking into research from different scientific and technical advice institutions for global governance (Panel on Scientific and Technical Advice for Global Governance).

BBNJ Secretariat

Regarding the functions of a secretariat laid out Article 51 of the draft text, delegation’s views converged to streamline Paragraph 4 and 8 (a and m) and delete details in the provision which can be accommodated elsewhere. While delegations quickly agreed to the need for and overall functions of the secretariat, different views were expressed on whether a new secretariat should be established, or an existing institution could take over this task. Some delegations suggested exploring the possibility of UNDOALOS becoming the secretariat of the BBNJ Treaty. It was clear that UNDOALOS would require significant strengthening of structure and resources to fulfill the new functions. In any case, it was noted that if a new secretariat was to be established, UNDOALOS could operate as the interim secretariat.

Clearing House Mechanism

Similar to discussions for the STB, also for the Clearing House Mechanism (CHM), there was no question about its indispensable role for implementation, but the specifics were not agreed on and detailed language on the modalities was preferred to be deleted in the draft text (Art 51) and for the COP to decide.

There was some support to have either the future secretariat or the existing IOC-UNESCO (Paragraph 6) manage the CHM, or to also to leave this open for further debate in the COP. Some delegations addressed the issue of confidentiality for the work of the CHM as its main task is open data sharing. It was largely preferred to include an additional provision in Paragraph 7 to avoid conflicts between these principles. What remains clear up to this point is that the CHM needs “a human element”, an administration with staff going beyond a mere database which can be accessed via a website. It was highlighted that the CHM needs to be able to show initiative, for example in establishing partnerships across the world regions as to future-proof the agreement.

Funding for the High Seas Treaty

Throughout the discussions, three main streams emerged for funding to happen within the BBNJ agreement 1) funding for developing states’ representatives to participate further meetings (e.g. in the COP); 2) funding to make effective implementation of the agreement possible for states with capacity needs through CBTMT and benefit-sharing; and 3) funding for the institutional framework of the BBNJ treaty.

While developed countries made it clear that they are not willing to commit to mandatory funding in the first two streams, they rather supported mandatory funding for setting up the necessary institutions including a financial mechanism. The financial mechanism (Art.52) was seen as another main pillar of the institutional framework of the new Treaty but views diverged regarding the desirable sources:

Proposals were made for a voluntary trust fund (Para 4) and a special fund (Para 5), or to task the Global Environmental Facility (GEF) as core funding body under direction of the COP. A representative of the GEF was given the word to explore the possibility of the GEF becoming the financial mechanism of the BBNJ Treaty. While this was welcomed in general, the text as it currently stands in the draft would need to be re-formulated to enable further engagement with the GEF. In relation to funding it was highlighted that the GEF already contains a number of financing streams for ocean management. One delegation noted that a comprehensive overview of the current landscape of ocean funding would be useful. This demand was well-received by the presidency of the conference who offered to prepare information in this regard.

How to be prepared for potential disputes that arise about the High Seas?

International agreements generally have a provision about dispute settlement, to address potentially arising conflicts about the subject matter. In negotiations about the dispute settlement for BBNJ, there is up until now no agreement on how this should look like. UNCLOS parties see the provision on dispute settlement of the convention as a good basis to be translated into the BBNJ agreement, as it was done previously in the case of the United Nations Fish Stock Agreement (UNFSA). However, non-parties to UNCLOS raised their voices against such an approach with the concern to be somehow bound to UNCLOS obligations. They categorize the BBNJ agreement as an “environmental treaty”, and propose to take environmental treaties as a drafting example instead. A proposal was made to submit joint disputes, like in the UNFSA, or to establish an additional chamber in the International Tribunal on the Law of the Seas (ITLOS) for disputes arising from the BBNJ Treaty. It was noted that it would not be necessary to enshrine this in the BBNJ Treaty as ITLOS can decide to establish such a chamber itself. A number of states proposed to authorize the COP to request an advisory opinion by ITLOS, which was however also met with opposition by others.

How to make words come into action?

States showed general support for Article 53 on implementation and compliance, stating that states shall take the necessary legislative measures to ensure implementation. A cross-regional proposal for an implementation and compliance committee was welcomed by many. States highlighted that such a committee would act in a non-adversarial, non-confrontational way. It was agreed to consider best practice examples for compliance committees of other agreements to see the value of such a mechanism.

Defining what is being negotiated…

At the end of the conference, delegates embarked on discussing the use of terms (Art. 1). Although this agenda item was kept until the last day of the conference still, at this stage, a number of delegates referred to this discussion being premature, as first, the substantive parts would have to be agreed on. And indeed, the disagreements over how to define MGRs and ABMTs reflected to a large extent the divides that were expressed in the substantive parts when delegates discussed the content of the respective chapters. Hence, no significant progress on defining the use of terms was made.

Evaluating activities on the High Seas through EIAs:

As the last package item, EIAs were discussed on Wednesday and Thursday. The facilitator decided to put the individual provisions into clusters in which many different provisions were discussed jointly. Under the first cluster, delegates were invited to discuss the criteria and threshold for EIAs, addressing Art. 24 (Thresholds and Criteria), Art. 27 (Areas identified as ecologically or biologically significant or vulnerable), Art. 29 (List of Activities). Under the second cluster, the internationalization of EIAs was discussed, addressing the question to what extent the bodies of the BBNJ instrument or states should oversee the conduct and evaluation (Art. 30 (Screening), Art. 37 (Consideration and Review)) of an EIA and who can ultimately decide on going ahead with an activity (Art. 38 (Decision-making)), as well as how the activity and its impacts shall be observed and communicated (Art. 39 (Monitoring), Art. 40 (Reporting), Art. 41 (Review)) and how it sits within the EIA processes of existing IFBs (Art. 23 (Relationship to other IFBs)). The EIA Chapter was concluded with discussions on Art. 28 (Strategic Environmental Assessments) on Thursday afternoon.

A cross-regional group of states presented a proposal to have a tiered approach for assessing an activity based on the threshold used in the Madrid Protocol on the Environmental Protection to the Antarctic Treaty for triggering an EIA. This cross-regional proposal of the tiered approach foresees that a state should firstly screen whether a proposed activity is “likely to have more than a minor or transitory effect on the marine environment”. If this threshold is reached, an EIA under the BBNJ agreement will be necessary and different levels of internationalization throughout the EIA process are envisaged. In terms of decision-making, the COP would be responsible for determining whether the activity at hand may proceed, which remained a contested provision in the draft agreement. Many states however, largely from the global North, opposed this proposal and showed unwillingness to go beyond the threshold of UNCLOS which states that an EIA is required “when States have reasonable grounds for believing that planned activities under their jurisdiction or control may cause substantial pollution of or significant and harmful changes to the marine environment”. These delegations also fiercely opposed the proposal to let the COP decide whether an activity may proceed and stated that the EIA process should be purely state-led and also decided by the state under whose control the activity should take place. This would leave the BBNJ instrument with virtually no power to evaluate EIAs or prevent any harmful activities from taking place. Arguments that the state which sponsors the activity under assessment may encounter a conflict of interest assessing said activity itself or be inclined to conduct a rather “complaisant” EIA were ignored.

Discussions also addressed whether areas that have already been identified as vulnerable (ecologically and biologically sensitive areas – EBSAs) would make an EIA compulsory, where some delegations noted that a specific provision addressing EBSAs was not necessary as activities in these areas would automatically meet the threshold.

Main points of divergence

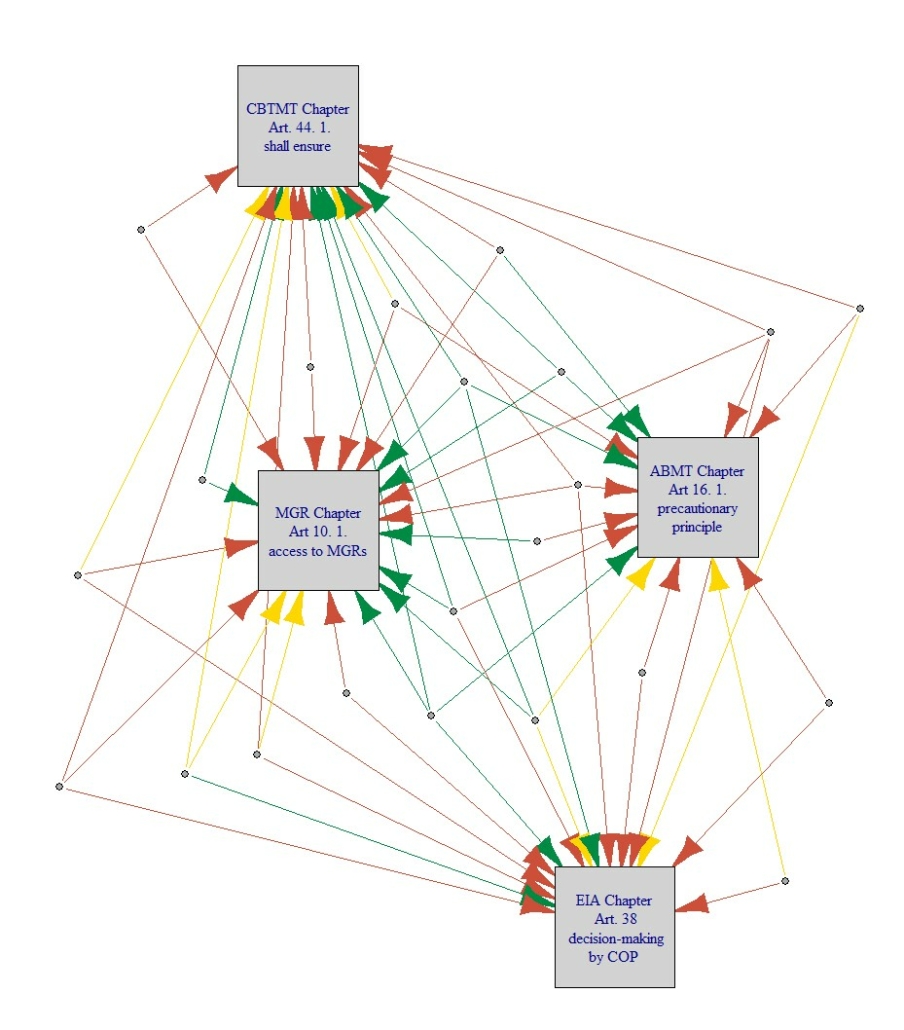

While some progress was made during the two-week negotiations, and delegations showed arguably more flexibility than in previous sessions, deep divergences remained over some of the main issues. In the following Figure 1, we show the disagreement among and flexibility of delegations over one provision from each package item which represent key points of divergence. The states are shown as circles that support (green arrow), oppose (red arrow) or are flexible (yellow arrow) towards the key Treaty provisions.

In the MGR package item, delegations mainly disagreed over what should fall under the definition of MGRs and how to regulate access and benefit-sharing thereof (see MARIPOLDATA Blog). This divide over how to approach the regulation of MGRs was represented in the positions towards the brackets in the draft text under Article 10.1. where many developing countries preferred the wording of “access” to MGRs whereas many industrialized countries supported the more narrow wording “collection of” MGRs. When referring to “access”, developing countries sought to include marine genetic resources in any form – going beyond the physical sample, also including genetic sequence data, digital sequence information and derivatives – whereas the formulation “collection of” refers exclusively to the moment when a sample is taken from the High Seas and leaves possible other forms of MGRs unregulated. This division was particularly contentious regarding benefit-sharing of MGRs.

In the ABMT/MPA chapter, countries disagreed over how broad the mandate of the BBNJ Treaty should be to designate MPAs. While this divide was voiced throughout many different provisions, it can be clearly seen in the diverging positions on whether the instrument shall apply the precautionary principle. Enshrining this principle in the ABMT/MPA Chapter would mean that the BBNJ instrument could identify and propose areas that require protection more progressively, particularly in situations of uncertainty. The precautionary principle states that conservationist action shall be taken immediately because waiting for compelling evidence of harm may be too costly for the environment (see IUCN Guideline).

Main disagreements also concern how the new BBNJ agreement can complement existing measures undertaken by other IFBs. Proponents of leaving the designation and management of MPAs solely in the hands of existing IBFs, such as regional fisheries management organizations (RFMOs) also oppose the inclusion of the precautionary principle in the text. As seen in the use of terms discussions, actors additionally disagree on the definitions of ABMTs and MPAs and whether or not to include – apart from conservation – also sustainable use objectives.

In the EIA chapter, the main division among delegations was in defining the threshold (see above) and the role of the future BBNJ institutions (Scientific and technical body and COP) in decision-making (Art. 38) on approving planned activities for which EIAs were conducted. While the cross-regional proposal (mainly by developing states) suggested that the COP should have decision-making power, regarding the approval of activities of a certain scale, this BBNJ-decision-making was met with fierce opposition by many developed states who preferred unilateral decision-making powers by the state proposing the activity.

In the CBTMT chapter, divergence persisted over whether capacity building and transfer of marine technology should be mandatory or voluntary. This conflict was expressed in the wording of Article 44. 1 where developing countries wanted strong language (states “shall ensure” capacity building) and industrialized opposed this strong wording and supported “shall promote” instead.

Figure 1 – The disagreement in 4 key provisions visualized. States are represented by the small grey circles and their position towards four key provisions is shown by the coloured arrows. Red -> opposition, green -> support and yellow -> flexibility. Because of the “informal informals” negotiation format we cannot name the states that expressed these positions.

Figure 1 shows that generally, the core of the disagreements and the division between developing and developed world in each of the package items has remained the same since IGC 1. Click here to have a detailed and interactive look at the key disagreements of Figure 1.

Closing remarks and Outlook

In the final round of statements on Friday, 18th March, many states used the opportunity to highlight the negotiating progress that was made and to emphasize the key positions for their delegations. Many statements highlighted the need to protect the ocean and to regard biodiversity in areas beyond national jurisdiction as common heritage of humankind. For the first time in IGC 4, also NGOs were finally invited to give statements and they expressed their availability to facilitate discussions during the upcoming intersessional period in order to advance the exchange on key issues. The proposal to plan the next IGC in August 2022 was agreed upon. While some remained skeptical that the pending issues can be resolved in the next conference session with less than 4 months of intersessional period after the new draft text will be released in May – many expressed the ambition to finish the agreement in the upcoming session.

In light of the urgency to act, as one delegate stated it “while we are negotiating, the stressors on the ocean continue” – there will be the need for a strong and meaningful agreement that can guarantee the conservation and sustainable use of marine biodiversity of areas beyond national jurisdiction. If one sentence can stick with the delegates when they are traveling home which might loosen up existing struggles from the past 14 years of discussions about BBNJ it would be – while both objectives of conservation and sustainable use are to be achieved with the agreement, one needs to remember, as one state delegate put it: “without conservation there will not be sustainable use”.