State preferences in international negotiations – using the MARIPOLDATAbase to analyze countries’ shifting positioning towards monetary benefit sharing of Marine Genetic Resources in the BBNJ negotiations

Developed under the ERC-funded MARIPOLDATA project led by Associate Professor Alice Vadrot, the MARIPOLDATAbase catalogs Collaborative Event Ethnography (CEE) observations spanning the entire BBNJ (Biodiversity Beyond National Jurisdiction) negotiations from 2018 to 2023. It provides comprehensive primary data on actors, alliances, statements, treaty text, positions, networks, concepts, and meeting formats. By offering unprecedented access to these negotiations, the MARIPOLDATAbase supports researchers to empirically engage with the BBNJ negotiations and marine biodiversity governance more broadly. Showcasing the potential use of the MARIPOLDATAbase for teaching and research, students from the University of Vienna (Department of Political Sciences) present in this blogpost how they used it to trace, analyze, and understand the international marine biodiversity negotiation process.

Written by Lucas Steger & Timon Steger

Marine genetic resources hold immense potential for scientific discovery, pharmaceutical development, and biotechnology innovation (Dunshirn & Langlet, 2021; Krusberg et al., 2024). However, the governance of these resources, especially those found in areas beyond national jurisdiction (ABNJ), presents significant challenges, such as their sustainable use and legal governance. The Agreement for the conservation and sustainable use of marine biodiversity in ABNJ (BBNJ Agreement) aims to address these challenges by establishing a framework to regulate access and benefit-sharing of marine genetic resources.

View of ECOSOC room BBNJ IGC5. Photo by IISD/ENB | Diego Noguera

The negotiation on the modalities of access and benefit-sharing was one of the most contentious issues during the negotiations (Leary, 2019; Vadrot et al., 2022). The core dispute centred on the demand from Global South countries for monetary benefit-sharing (MBS), which faced significant opposition from many Global North countries. Although extensive research has been conducted on proposals to operationalize access and benefit-sharing for marine genetic resources (Humphries et al., 2020), the process of how and why an agreement was reached on this contentious issue have not yet been thoroughly explored. Our research aims to analyse the evolution of states’ positions on monetary benefit-sharing throughout the five-year negotiation process starting in 2018. The MARIPOLDATAbase allowed us to conduct a social network analysis (SNA) to visualize how countries’ positions towards monetary benefit sharing of marine genetic resources shifted over the course of the BBNJ negotiations and understand the fluidity of state positions in negotiations (Vadrot et al., 2022).

Methodology

The data used is part of the MARIPOLDATAbase, which is composed of fieldnotes collected during the BBNJ negotiations (Langlet et al., 2024). The data was collected by a team of researchers using a combination of participant and ethnographic observation and document analysis. Especially the approach of collaborative event ethnography (CEE) supported by notes from side events, draft texts and participant lists allowed to collect a detailed and large amount of data (Vadrot et al., 2024).

To filter out relevant data from the MARIPOLDATAbase, we filtered the statements to contain either of the words “benefit”, “monetary” or “sharing” leaving 1337 of the original 43,341 observations. These statements were coded in a qualitative process whether the statement made reflects a positive (1), neutral (0) or negative (-1) attitude towards monetary benefit sharing. The coding process gave us a chance to filter out unrelated statements which left us with a final coded dataset of 442 observations.

| “-1” | “0” | “1” | |

| IGC1 | 25 | 4 | 44 |

| IGC2 | 11 | 3 | 14 |

| IGC3 | 10 | 0 | 17 |

| online dialogue 1 | 15 | 4 | 42 |

| IGC4 | 33 | 30 | 51 |

| online dialogue 2 | 4 | 1 | 3 |

| IGC5 | 13 | 27 | 30 |

| IGC5.2 | 11 | 28 | 22 |

| All | 122 | 97 | 223 |

Table 1: Coded data per IGC

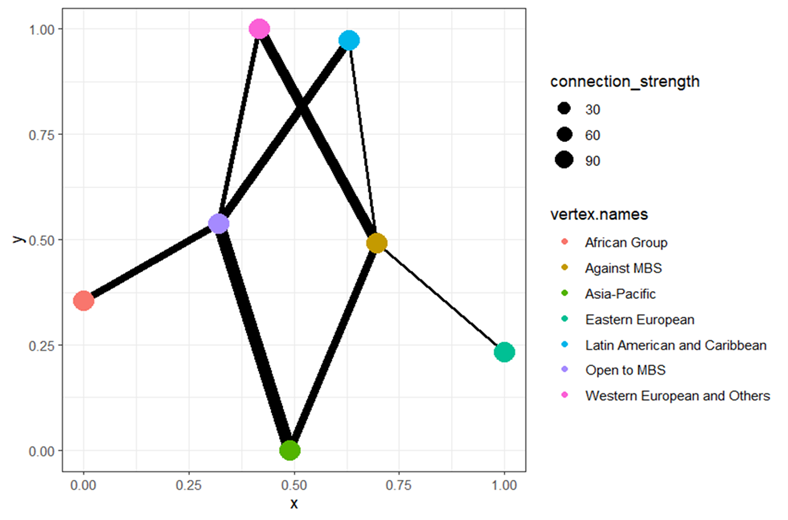

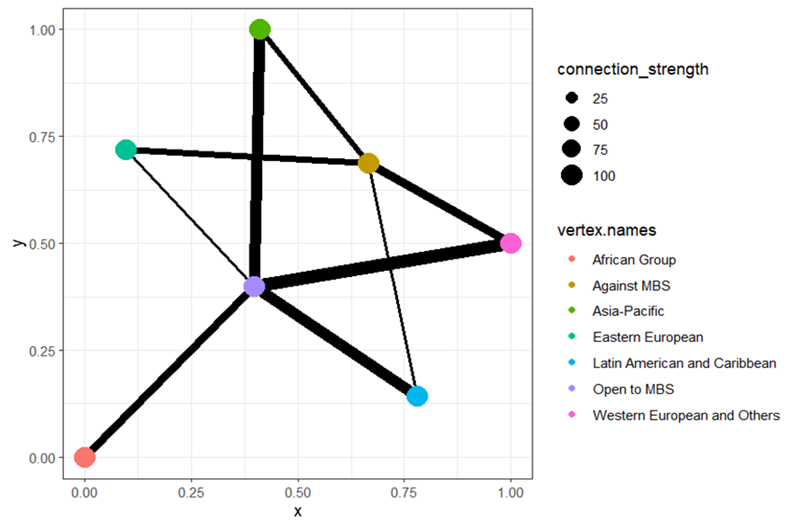

The coded data was then used to conduct a SNA for the different negotiation periods represented by intergovernmental conferences (IGCs). The nodes in the SNA are the five UN-groups and their positions towards MBS (open / against). The connections between the nodes are drawn only between an UN-group and the two predefined possible positions regarding MBS. The thickness of the connection is based on the number of statements being made, depicting how strongly an UN-group pushed their position regarding MBS and if it is more open or negative.

Key findings

Our analysis suggests that it is possible for UN-groups to shift their political position during the negotiation process, specifically in the concluding IGCs 5-5.2. While states often negotiate in larger alliances and do not want to give up on their goals during a negotiation, the analysis indicates that later in the negotiation process negotiators may prioritize coming to an agreement over pushing for their original positions. This makes UN-groups political positions arguably softer than what they might appear. Furthermore, if an UN-group is in opposition, this does not necessarily result in the blockade of a treaty element. Both of these findings are vital for interpreting progress during negotiations.

Additionally, we found some UN-group specific shifts in position during the negotiations:

- UN-groups started out by adhering to their core positions (IGCs 1, 2, 3): African Group, Asia-Pacific and Latin America and Caribbean being open to MBS and Western European and Others and Eastern European strongly opposing MBS

- At the midpoint of the negotiations (online IGCs & 4): Only very limited shuffling in UN-country groups’ positions. The African Group, Asia Pacific and the Latin American and Caribbean are still open to MBS, while Western European and Others and Eastern European are still opposing MBS

- By the end (IGCs 5 & 5.2): A shift in position by the Western European and Others UN-country group towards being open to MBS while the other UN-groups stayed loyal to their position

Figure 1: SNA for the first IGCs (1, 2, 3) (source: Authors)

Figure 2: SNA for the last IGCs (5, 5.2) (source: Authors)

It is important to remember that our findings do not show how content the different UN-groups are with the outcome of the negotiation as the statements were coded binarily. For example, the shift in position by Western European and Others does not necessarily mean that they are content with MBS. It would be more accurate to formulate that they changed their negative position towards MBS as their statements were more neutral and positive than before.

Outlook

While the dataset gives researchers the option to estimate UN-country groups positions towards topics that were discussed during the negotiation, country specific positions are harder to analyze. Because a large part of the negotiations took place in informal or online settings which were placed under Chatham House Rules, meaning that the state making a statement is left undisclosed, the data from these negotiation settings cannot be analyzed on the state-level.

Additionally, the ‘why’ behind the shifts in position of country groups was left unexplored. Possible reasons might be changes in the mobilization of relevant stakeholders in the Global North countries or changes in influential governments in countries like Germany or Australia (Downy, 2012). Something that might have further pressured decision-makers are the increasing urgency and costs of climate change.

References

Downie, C. (2012). Toward an Understanding of State Behavior in Prolonged International Negotiations. International Negotiation, 17(2), 295–320. https://doi.org/10.1163/157180612X651458

Dunshirn, P., & Langlet, A. Governing knowledge in relation to Marine Genetic Resources and COVID-19 vaccines. MARIPOLDATA blogpost, 04/05/2021

Humphries, F., Gottlieb, H. M., Laird, S., Wynberg, R., Lawson, C., Rourke, M., & Jaspars, M. (2020). A tiered approach to the marine genetic resource governance framework under the proposed UNCLOS agreement for biodiversity beyond national jurisdiction (BBNJ). Marine Policy, 122, 103910.

Krusberg, T., Schildt, L., Jouffray, J. B., Zhivkoplias, E., & Blasiak, R. (2024). A review of marine genetic resource valuations. npj Ocean Sustainability, 3(1), 46.

Langlet, A., Vadrot, A.B.M., Fellinger, S., Dunshirn, P., Ruiz Rodriguez, S. C., Tessnow-von Wysocki, I., 2024, “MARIPOLDATAbase (SUF edition)”, https://doi.org/10.11587/0XXZ0V, AUSSDA, V3

Leary, D. (2019). Agreeing to disagree on what we have or have not agreed on: the current state of play of the BBNJ negotiations on the status of marine genetic resources in areas beyond national jurisdiction. Marine Policy, 99, 21-29.

Vadrot, A.B.M. Langlet, A. Tessnow-von Wysocki, I. (2022). Who owns marine biodiversity? Contesting the world order through the `common heritage of humankind´ principle. Environmental Politics 31(2): 226-250