Light on the Horizon? Negotiations to complete a new Marine Biodiversity Treaty resume

By Ina Tessnow-von Wysocki, Arne Langlet and Alice Vadrot

Please cite as: Tessnow-von Wysocki, I., Langlet, A., Vadrot, A. (2022). Light on the Horizon? Negotiations to complete a new Marine Biodiversity Treaty resume. MARIPOLDATA Blog post. DOI:10.25365/phaidra.331. Retrieved from https://www.maripoldata.eu/light-on-the-horizon-negotiations-to-complete-a-new-marine-biodiversity-treaty-resume/

The negotiations for the legally binding agreement on the conservation and sustainable use of marine biodiversity beyond national jurisdiction (BBNJ) go into the next round. The fourth Intergovernmental Conference (IGC) had been postponed over 2 years, due to the Covid-19 pandemic. Last week, negotiators from around the world could finally get back together to formally pick up their work on the BBNJ Treaty. MARIPOLDATA is following the discussions online, as access to the UN premises was not granted to observers.

Jumping right into negotiation mode – and into cold water

Some efforts have been made to keep momentum throughout the 2 years of intersessional period (High Seas Treaty Dialogues and the Virtual intersessional work). However, no formal progress could be made with the “informal” conversations not being formally recognised as negotiations and, thus, not transferred into new proposals for legal text.

On March 7th, therefore, negotiators went back to the draft text from November 2019, and skipping opening statements, to “jump right into negotiation mode”. Almost. The terrible developments in Ukraine did not go by the BBNJ negotiations and caused many delegates to show solidarity with Ukraine before they turned their attention to the negotiation agenda and procedures.

Initial confusion about how to access the conference room papers and new procedures to submit textual proposals could quickly be overcome. But there was something else different this time: Observers were not allowed in the room. Due to Covid-19 regulations, the number of representatives per delegation was reduced to two per state delegation, leaving observers excluded from the conference room.

Observers include intergovernmental organisations, such as regional fisheries management organisations, the United Nations Environment Program, the International Seabed Authority, or the Convention on Biological Diversity- actors that have previously been present in the room and actively engaged in the discussions. Moreover, observers consist of representatives from media, industry and environmental non-governmental organisations – including an alliance of more than 40 NGOs (the High Seas Alliance) which have been contributing significantly to the exchange among governments during the intersessional period. Last but not least, the whole academic community from research institutes and universities, representing the social and natural marine science communities from around the world, including DOSI (the deep ocean stewardship initiative) or the International Studies Association were – despite their successful registration – not allowed to access UN premises. Registered observers could follow the negotiations online and email their statements to the Secretariat for publication on the Conference Website but not attend and intervene in the sessions, which was criticised by several state delegations.

The MARIPOLDATA Team members Ina Tessnow-von Wysocki and Arne Langlet are following the negotiations from the office in Vienna.

The MARIPOLDATA Team members Ina Tessnow-von Wysocki and Arne Langlet are following the negotiations from the office in Vienna.

Half- way into the negotiations: How was the time used?

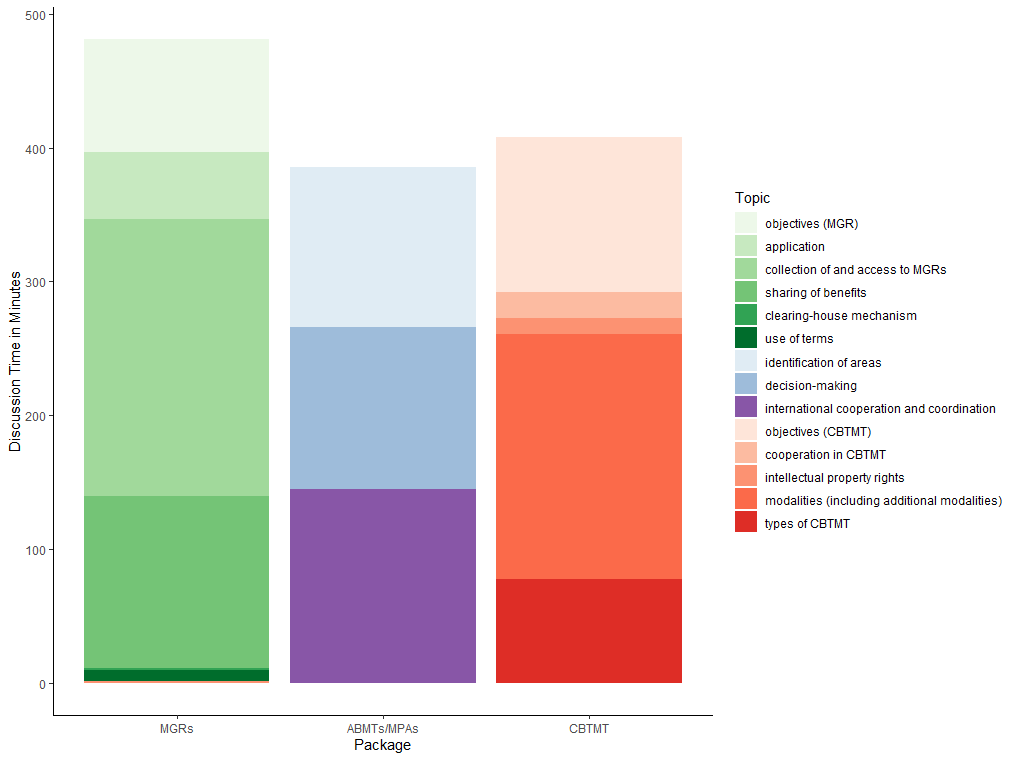

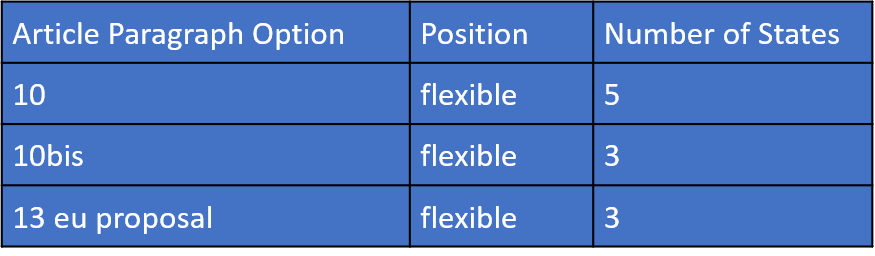

Taking stock of the progress of the first week of negotiations, the package elements Capacity-building and Transfer of Marine Technology (CBTMT), Marine Genetic Resources (MGRs) and Area-based management Tools (ABMTs), including Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) were addressed by negotiators. Using our systematic fieldnotes taken on the basis of ethnographic data collection- MARIPOLDATA can display the net speaking time of delegates on the different articles of the draft text, as illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1 – Discussion Time by Topic

Whereas on the ABMTs/MPAs, speaking time was relatively equally divided among the three articles under discussion (identification of areas, decision-making and international cooperation and coordination), the most negotiation time on both MGRs and CBTMTs focused on a single article. In the MGR chapter, the article Collection of and Access to MGRs and in the CBTMT Chapter the article Modalities (with the link to the article on additional modalities) took up considerably more time to discuss than the remaining issues.

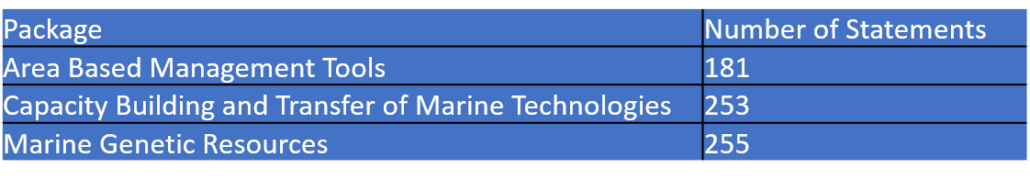

While delegates spent slightly more time discussing the chapters Negotiation of MGRs and CBTMT chapters were characterized by lengthier discussions and significantly more interaction between state delegates (see table 1) indicating that these were the more controversial topics in the first week. In the following sections we give an overview of the topics discussed and identify areas of convergence and divergence of views.

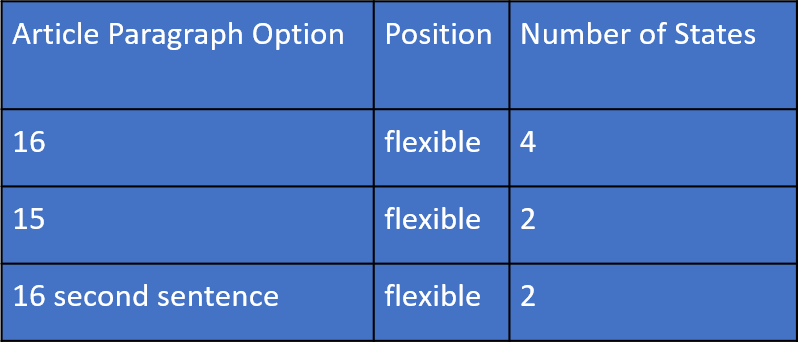

Table 1 – Recorded Number of Statements per Package Item

How to build capacity and transfer marine technology?

Technology (CBTMT). Main discussion points were whether CBTMT should be country-driven or needs-driven. While there was general convergence of views that duplication should be avoided when it comes to research projects and funding, opinions were raised that a positive phrasing might be more appropriate, along the lines of “building on existing”, to avoid complicated discussions around the definition of “duplication”. Another main point was to what extent modalities of CBTMT needed to be specified in the BBNJ treaty text as opposed to tasking the COP with the development of such. The IOC criteria and guidelines on the transfer of marine technology were repeatedly mentioned as best practice and valuable guidance to the COP. The main complication remained with the question whether or not CBTMT needed to be an obligation or voluntary. Japan and UK expressed concern that unless the voluntary vs. mandatory question was settled, it would be difficult to decide on concrete provisions in this article. Proposals were raised to merge Art. 43 and 44; or 44 and 45 by several delegations.

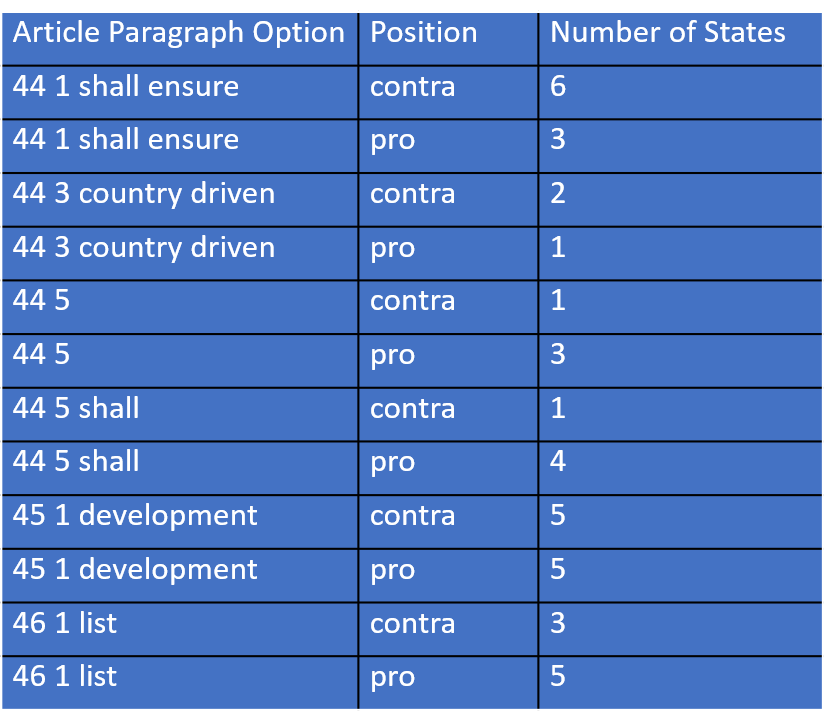

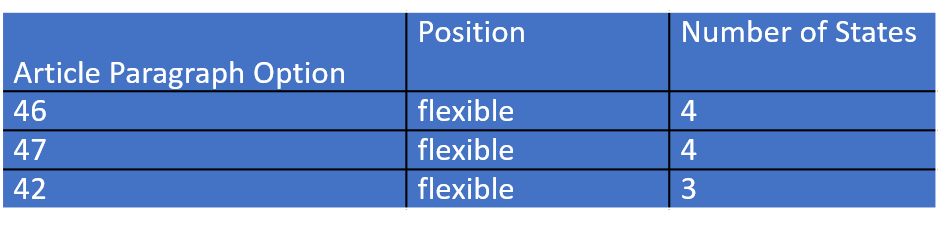

The second day started right where delegated left off the day before: A possible indicative, non-exhaustive list of types of CBTMT was discussed under Art. 46 to which states voiced contrary positions (Table 2). Meaningful for most developing countries, developed countries were skeptical of the usefulness of such a list in the treaty text and mentioned their concern over difficulties in amending it over time. The discussions ended with the three options: a) list in the draft text(Art. 46 1; Art. 46 2) and/or annex ii, b) no list c) list in official report of the conference but not in the agreement as such.

Table 2 – Contentious Articles in the CBTMT Chapter

Other contentious topics regarding the Article on modalities were whether the agreement shall ensure or promote the access to CBTMT (Art.44 (1)), and potential obligations for the COP to develop detailed modalities (Art. 44 (5)) (see Table 2). Delegations needed to sit together after the end of the sessions to develop some creative language in finding a middle ground between the strong and mandatory language of “shall ensure” and the loose language on the other end of “shall promote” and consider the different tasks that the COP should be covering in light of the whole agreement.

Table 3 – Articles with most flexible positions in CBTMT Chapter

When monitoring and review (Art. 47) in the section of CBTMT was discussed, some voices raised the call for having a single article on monitoring and review to cover the whole agreement, rather than in each section. Discussions surrounded whether subsidiary bodies should be mentioned in the article or left for the COP to establish if needed in the future. There was also some discussion on the term relevant actors vs. relevant stakeholders (Art. 47 (4)) regarding the scope of inclusion (e.g. the private sector). The Alliance of Pacific Small Island States (PSIDS) and the Caribbean Community (CARICOM) stressed the importance of monitoring control and surveillance to be taken up – possibly also in a different part of the agreement, which will be considered by the EU. Generally, states showed flexibility on the topic of monitoring (Art. 47), whether to have an article on types of capacity building (Art. 46) and on the objectives of CBTMT (Art. 42) (Table 3). Except for contrary voices from Russia and China, there was also agreement on including Strategic Environmental Assessments (SEAs). Despite some disagreements on the inclusion of a list of countries, there was overall support for reporting of CBTMT (Art. 47 (5)).

The negotiation room from the “online” perspective with only two representatives per delegation allowed in the room.

The negotiation room from the “online” perspective with only two representatives per delegation allowed in the room.

All agree that sharing is caring – But what and how, with whom, when?

After concluding the session on CBTMT, delegations had a short “switch over”- to exchange the responsible delegates from CBTMT to the Marine Genetic Resources (MGR) experts, as only two representatives were allowed in the room. Facilitation of the session was again guided by the president of the conference Rena Lee.

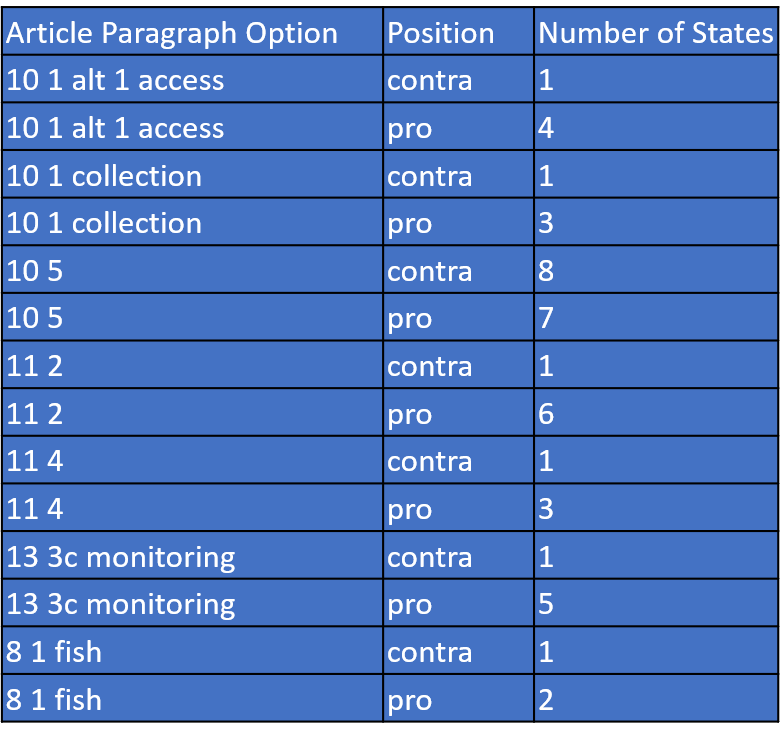

The discussion immediately showed the discrepancy between views on whether to talk about collection of or access to MGRs (Art. 10 (1 & 6), calling into the minds the deep divergence of views regarding access and benefit sharing (ABS) schemes. When discussions delved into the topic of how to set up a system for the collection/access to MGRs: two broad options were a) a notification and b) permit/license system. Broad agreement could be settled on a notification system– meaning that with a notification, the research cruise/collection/access activity could be undertaken and no prior permission needs to be issued. However, as there is a myriad of ways of such as notification scheme can look like, whether or not it would entail pre-cruise, post-cruise notification or both, the timeframes when those needed to be done and what should be notified, considering issues of confidentiality.

While delegations could agree on some sort of mandatory benefit sharing mechanism, the usual disagreement between whether or not benefit sharing would include only non-monetary or also monetary benefits came up under Art. 11 (2) (See Table 4) and was not resolved. The EU offered a suggestion to include financing of research projects as monetary benefit sharing. However, developed countries did not agree to the sharing of monetary benefits of products that derived from MGRs in ABNJ. Overall, disagreement on the inclusion of in silico digital sequence information and genetic sequence data could not be settled.

Table 4 – Contentious Articles in the MGR Chapter

Article 10, paragraph 5 caused disagreement on two issues: whether it is necessary to specify that state parties shall take the necessary legislative, administrative and policy measures to ensure the application of the MGR chapter in particular, or sufficient to have such a provision in general for the whole instrument. The heavier disagreement however was on the question whether adjacent coastal states should have particular rights to be notified and consulted when activities in relation to MGRs are undertaken in areas adjacent to their waters (See Table 4), a conflict which was responded to with the idea of an automatic system to notify all states.

Despite the differences, there were moments of efforts for approaching agreement. If we had not heard the facilitator giving Iceland the floor, one could have thought the facilitator had spoken the words of encouraging “solutions that the majority of us can accept, maybe not what we had in mind when we first joined the table, but what accommodate most. […] creative ways to accommodate everybody’s interests” (MARIPOLDATA Fieldnotes, March, 7th, 2022, 4:11 pm EST).

Discussions went on into the next day (day 4), where is became clear that developed countries were not supportive of the term “monitoring” and rather opted for “transparency”. Brazil on behalf of the Core American Country Group (CLAM) presented a proposal for an access and benefit-sharing (ABS)scheme based on the idea to track and trace the use of MGRs, and the EU proposed an ABS scheme with a focus on transparency. A number of delegations expressed their flexibility in regards to the EU proposal. Delegations also showed flexibility to include the Article 10bis which was proposed by the PSIDS on the rights of traditional and indigenous knowledge holders in relation to MGRs.

Table 5 – Articles with most flexible positions in MGRs Chapter

The next difficult conversation evolved around whether or not and to what extent the agreement should apply to fish or fishing activities (Art. 8 (1)). No state delegation wanted fishing or fisheries to be regulated by the new agreement, however – apart from some few exceptions – there was strong support for fish to be covered in the agreement, as it is part of biodiversity.

When water turns into ice: Negotiations in ABMT session freeze

Without reaching agreement on the key issues of which kinds of benefits to be shared and whether or not to include monetary benefits, the agenda moved on to Area-based Management Tools (ABMTs), including Marine Protected Areas (MPAs). The atmosphere in the room changed completely, and convergence on a range of issues could be found. There was general agreement on taking precaution and a potential indicative list of criteria was debated. All delegations speaking in favour of the need for science-based criteria and including a reference to traditional knowledge of Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities. Some drafting and merging of provisions from Art. 16 (4) with Art. 17 were discussed and the session ended early and with friendly laughs among colleagues as if they were all representing the same delegation.

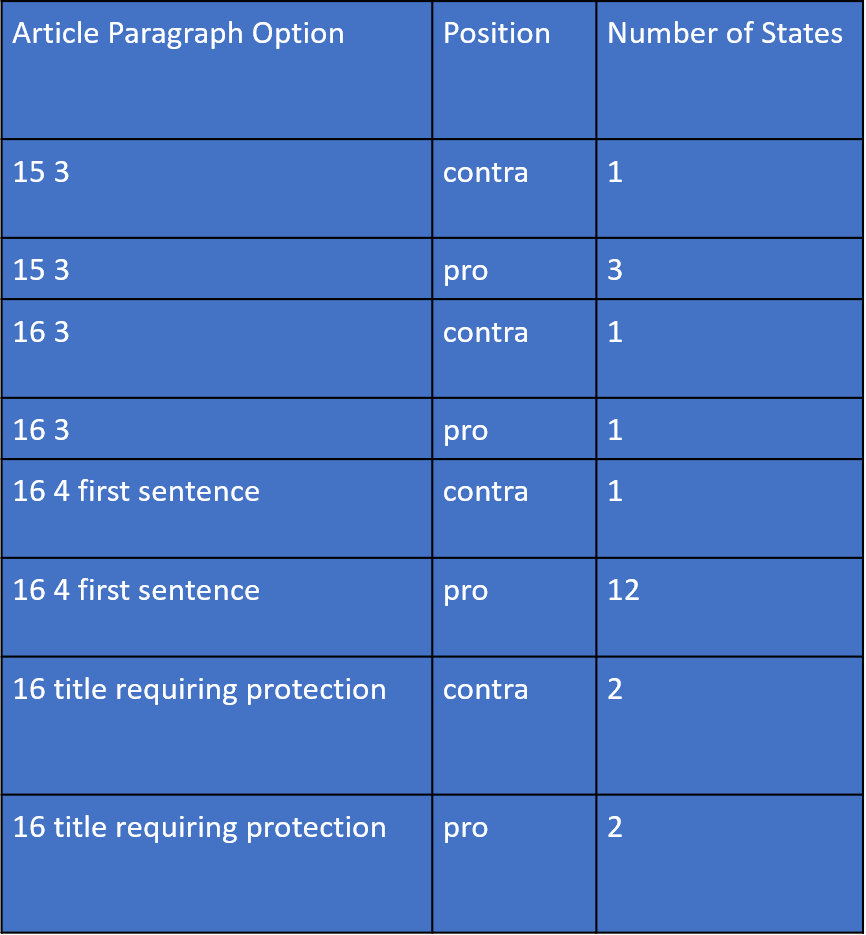

As lovely the previous session had ended, as cold and confrontative negotiations started the next morning with the statement by Russia that – while some convergence might have happened – no consensus was reached on the previous ABMTs session. Delegates and observers knew that the provisions on the relationship with existing instruments was a topic of confrontation (Art. 15), which was yet to come. Our analysis shows states expressed contrary positions particularly in Article 15, paragraph 3 on whether states shall make arrangements for consultation and coordination with other instruments (See Table 6). Several delegates circulated in the debate about the definition of (not) undermining, while some were referring to undermining institutions and others stressing that this discussion should focus on not undermining mandates and the effectiveness of measures. Confusion about the definition of complementarity was responded to with useful examples and best practices from cooperation between NEAFC and OSPAR. The difference between relevant and competent global, regional, subregional and sectoral institutions, frameworks and bodies (IFBs) was highlighted by Monaco, who preferred the term relevant (incorporating a larger number of stakeholders) in the consultation process for ABMTs, including MPAs, and competent IBFs when it comes to the issue of undermining. There was also disagreement whether the title of Article 16 should read “Identification of areas” or “Identification of areas requiring protection” and whether to refer to a list of criteria in annex 1 (Table 6).

Table 6 – Contentious Articles in the ABMTs/MPAs Chapter

The change of atmosphere in the room was visible, but then some states showed almost surprising flexibility – notably Iceland – no longer holding onto their traditional position in the negotiations (of a strict regional approach), introducing constructive proposals. “We have been on a more regional approach [refers to Art. 19, Alt.2], but the time of binary is over” (MARIPOLDATA Fieldnotes, Iceland, March 11, 2022, 4:08 pm EST). These sparks of hope for consensus brought light into the otherwise split discussions. Some states showed flexibility in regards to the general inclusion of Articles 15 and 16, and indicated that the second sentence in Art. 16 – referring to the best available science – could potentially be a way forward (Table 7).

Table 7 – Articles with most flexible positions in ABMTs/MPAs Chapter

Diving into the second week of negotiations

Delegates showed some flexibility on certain issues and negotiations started removing brackets in the draft text – meaning to progress the text towards consensus. At the same time, however, it became clear that initial divergence on key issues – such as the nature of benefits to be shared and its process, whether to protect biodiversity from impacts of activities in general or just from high seas activities or how to situate BBNJ in the landscape of existing instruments – could not be resolved in the lengthy intersessional period and remain until this day. Without anyone daring to say it out loud, it is in everybody’s minds – in order to have agreement on these issues, one more week seems to be too little time.

The week starting from the 14th of March, 2022 will cover the remaining package element of Environmental Impact Assessments, as well as cross-cutting issues and will allow time for stock-taking. What else will be new? After continuous pressure from the High Seas Alliance and statements by state delegates, calling for civil society participation, three representatives of observers will now be allowed in the room.

Observations of the first week of negotiations show that the contrasting views of the past continue to divide current state positions. For example, the eternal and profound divide between supporters of the common heritage of mankind principle and their opposition is still present when delegates discussed the MGR topic. The hardened position of much of the developing world on the MGR and related CBTMT topic can be attributed to the deep mistrust that has built since the entry into force of UNCLOS. As the delegate of Bangladesh eloquently expressed: developing countries are disappointed that even though capacity building is foreseen in UNCLOS, it has not materialized since its entry into force 40 years ago (MARIPOLDATA Fieldnotes, Bangladesh, March 7, 2022, 4:23 pm EST). This may explain why developing countries insist on a great level of detail in the CBTMT chapter combined with obligatory language. However, one may also recall that the conservation of marine biodiversity is one of the main goals of this treaty. Discussions on the establishment of ABMTs, including MPAs and the conduct of EIAs, essential to achieve this aim however, have been taken a backseat in the first week of negotiations. The BBNJ Treaty presents a unique opportunity to establish a global network of MPAs that are globally recognised and in the best case jointly monitored by regional and global institutions. Therefore, it is regrettable that advances in the negotiations are held back by disagreements over the exploitation and allocation of resources, rather than focusing on a holistic solution for ocean protection.

This is now the time for delegations to approach one another with more flexibility and the realisation that this agreement is at the end of the day not for one country alone, but in the joint interest of all and future generations to come. This means that countries should acknowledge the deep material inequalities that exist between the developed and the developing world in exploring, exploiting and protecting the ocean. This instrument can address these – to the benefit of all. At the same time, while discussions on MGRs and potential benefit-sharing as well as the monitoring of such efforts are important, countries should not lose sight of one of the main objectives of this negotiation process, namely the conservation of marine biodiversity. We saw also that, although some states indicated to be flexible about certain provisions, there is much room for improvement in making “flexible our new favorite word” as the President of the conference Rena Lee suggested to delegations.