MARIPOLDATA gathered scientists and policy-makers in the Intersessional Period of the new BBNJ agreement at the Earth System Governance in an Innovative Session: United Nations Negotiations for the Future of Marine Biodiversity: A conversation among Academics and Practitioners on the BBNJ Negotiations, chaired by Assoc. Prof. Dr. Alice Vadrot and Ina Tessnow-von Wysocki.

A recording of the panel is now available here:

In the framework of the innovative panel, scientists met with national delegates, as well as representatives of non-governmental organisations that are participating in the negotiations to:

- discuss the current stage of the BBNJ negotiations, the potential final agreement, and the role of the intersessional work;

- share their expert knowledge and experiences on the current state and development of the BBNJ negotiations; and

- reflect on new findings of BBNJ research and current political developments within the BBNJ process.

Keeping the Momentum for Marine Biodiversity Negotiations

What is happening while Marine Biodiversity Negotiations are being postponed?

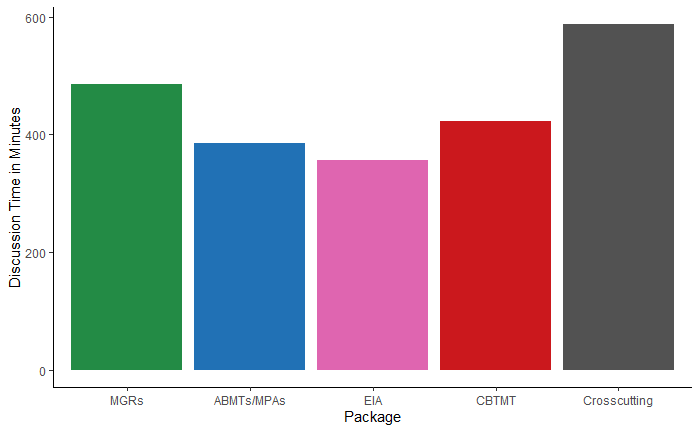

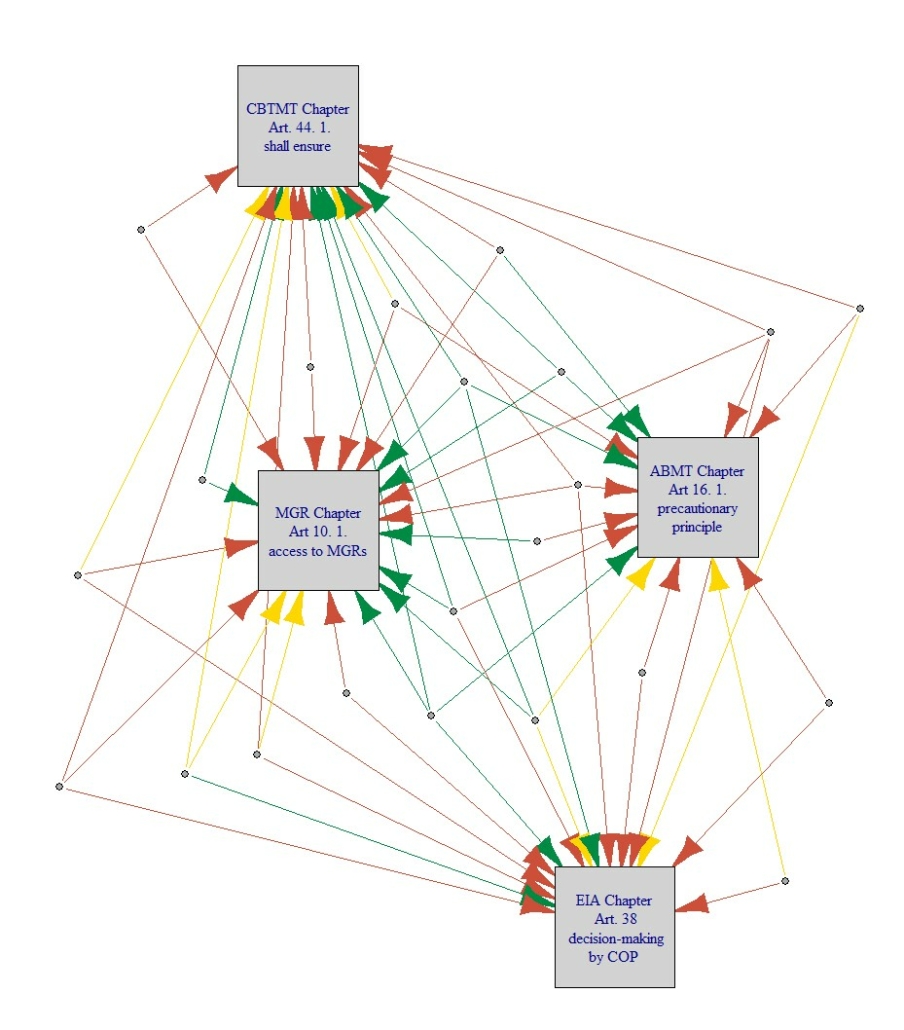

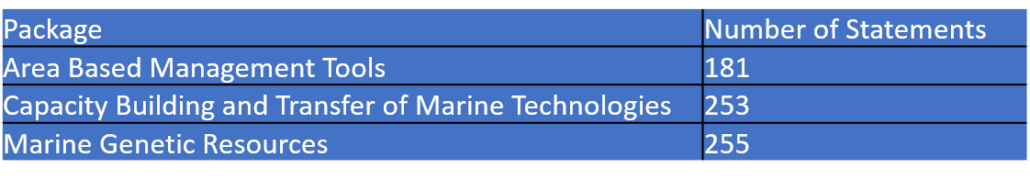

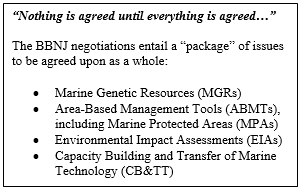

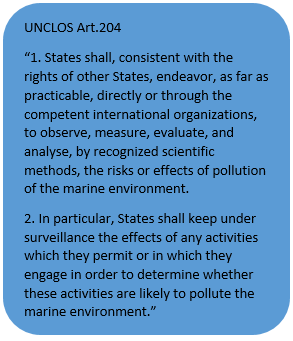

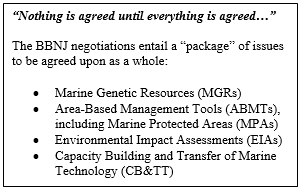

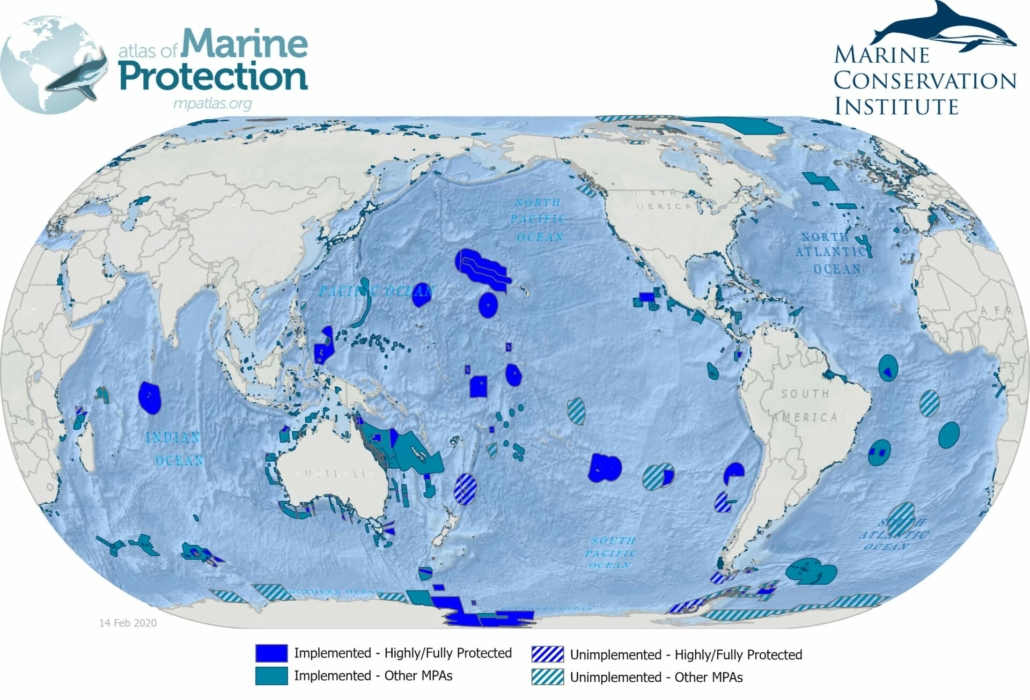

The United Nations are currently negotiating a new an international legally binding instrument under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea on the conservation and sustainable use of marine biological diversity of areas beyond national jurisdiction (BBNJ). The new treaty is expected to set new regulations for marine genetic resources (MGRs), area-based management tools (ABMTs), including marine protected areas (MPAs), environmental impact assessments (EIAs) and capacity building and the transfer of marine technology (CB&TT) (Tessnow-von Wysocki & Vadrot, 2020). Originally, the aim was to terminate negotiations in March 2020, but due to the Covid-19 pandemic, negotiations were postponed continuously and the next tentative date is March 7th-18th 2022.

There are several initiatives happening in the intersessional period – the time in between the conferences – to keep the momentum. The most prominent initiatives include the Intersessional Work[1], organised by the UN Secretariat as an online platform for BBNJ participants to exchange views on package elements, and guiding questions that have been formulated by the facilitators of the conference and provide virtual webinars on BBNJ topics. Moreover, the governments of Belgium, Costa Rica, Monaco and a number of non-governmental organisations (NGOs) (the High Seas Alliance) have organised High Seas Online Dialogues[2], in which BBNJ participants can interactively engage verbally in 3-hour-long sessions on selected topics.

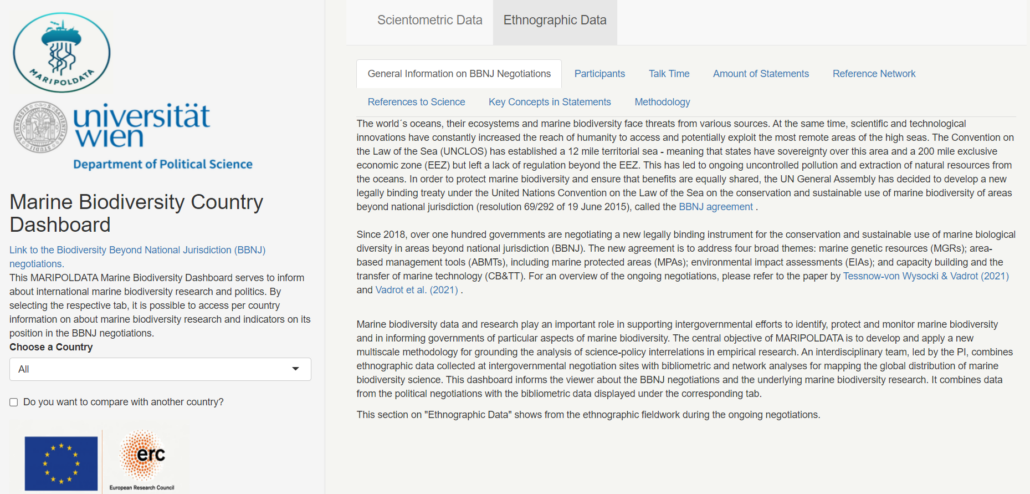

The MARIPOLDATA team facilitated an inter- and transdisciplinary dialogue among the scientific community and fostered the science-policy interfaces for BBNJ by introducing a number of outputs to inform the negotiations and keep the momentum (See: MARIPOLDATA Ocean Seminars; MARIPOLDATA BBNJ Governance Database ; MARIPOLDATA Country Dashboard).

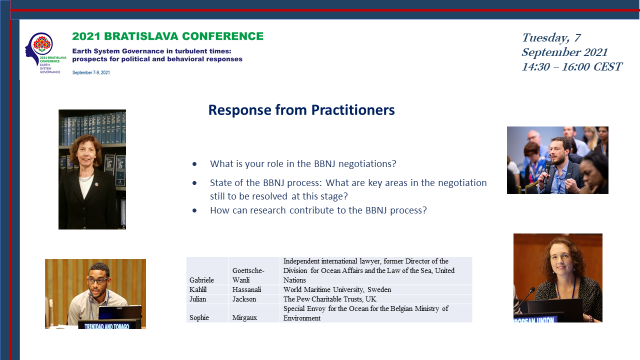

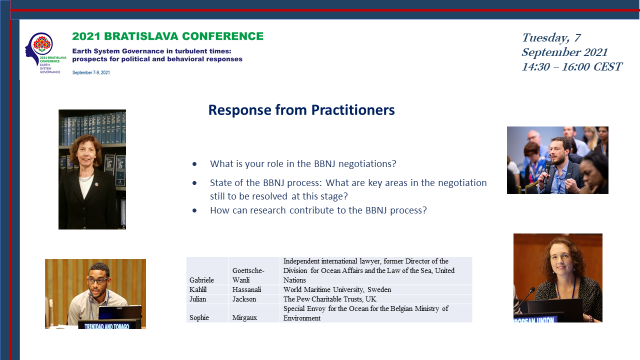

As part of the Earth System Governance (ESG) Conference on September 7th 2021, the MARIPOLDATA team brought together 10 scientists and practitioners on BBNJ to discuss recent developments in the BBNJ negotiations, to identify key areas still to be negotiated in each of the package elements and cross cutting issues and point to how research can contribute to the BBNJ agreement. This innovative panel brought together the different groups engaging in the BBNJ process, including social and natural scientists researching on BBNJ, as well as practitioners who are actively engaged within the negotiation process. It provided an opportunity for a fruitful exchange on different perspectives to existing research and new linkages of research findings among diverse disciplines.

Recent BBNJ Research Findings and Ongoing Projects

Scientists from the fields of Law, Political Science, International Relations, Ocean and Coastal Governance, Environmental Studies and Deep-Sea Biology were invited to join the panel and share their most recent scientific findings related to the BBNJ process.

Researching the Deep-Sea

The deep-sea biologist Dr. Georgios Kazanidis shared experiences from the iAtlantic project, an EU-funded, multidisciplinary research programme seeking to assess the health of deep-sea and open-ocean ecosystems across the full span of the Atlantic Ocean. iAtlantic undertakes ocean observation, ocean mapping, ecosystem assessment, capacity building, and sustainable management of deep-sea and open ocean ecosystems in the North and South Atlantic Ocean.

He particularly emphasised the need to collaborate among different disciplines and geographical regions, include early career researchers in marine scientific research[3], and organise joint workshops among scientists, industry, NGOs and policy-makers.

Following the panel, he shared his co-authored study on a common assessment framework for areas beyond national jurisdiction (ABNJ) that would enable comparable environmental assessments and facilitate monitoring (Orejas et al., 2020), which can contribute to ABNJ governance in the future. iAtlantic’s policy briefs communicate research findings in an accessible way, such as the ATLAS and iAtlantic Policy Brief – Changing Ocean State and its Impact on Natural Capital, explaining how ocean currents are impacting the climate, as well as locations and abundances of marine biodiversity at the surface and in the deep-sea (Spooner et al., 2020). The policy brief has also highlighted that continued observations and improved biological understanding are both needed to assess oceanographic change and its ecological implications.

The Design of the New Agreement

In the making of the new legally binding instrument for governing marine biodiversity in ABNJ, ongoing research surrounds questions on the design of the BBNJ agreement. Assistant Professor Dr. Elizabeth Mendenhall and Prof. Rachel Tiller are, with their research team colleagues, Elizabeth Nyman, and Elizabeth de Santo, particularly interested in what explains the final design of the BBNJ agreement. Prof. Mendenhall presented on the ambiguous definition of “areas beyond national jurisdiction” as regards the undecided extended continental shelf question, leaving the boundaries of ABNJ unclear. Moreover, while coastal states have sovereign rights over their continental shelves and their resources, there is legal uncertainty on the sovereignty over resources on the extended continental shelves. This includes the question of sedentary species but also on the access and use of marine genetic resources (MGRs) in these areas. The definition of sedentary species as “organisms which, at the harvestable stage, either are immobile on or under the seabed or are unable to move except in constant physical contact with the seabed or the subsoil” (UNCLOS, Art.77) is identified as quite ambiguous and could trigger further conflicts over the sovereignty over living resources on the extended continental shelf. If this is not addressed in the BBNJ agreement, the ambiguous definition of Art.77 would apply. Mendenhall could imagine a moratorium on the exploitation of MGRs in these ambiguous areas as one option to achieve legal clarity. She points to the fact that so far, there have been 88 submissions for the extended continental shelf, leaving many potential coastal states submissions for the future to define and the boundary of ABNJ ambiguous. Mendenhall suggests discussing this issue within the BBNJ negotiations to prevent misinterpretations over governance responsibilities and whether BBNJ governance will be different regarding the “Area” and the extended continental shelf, in the years and decades to come. Prof. Dr. Rachel Tiller shared her research on the Arctic and BBNJ and pointed to potential conflicts regarding resources in the Arctic ABNJ, including oil, gas or MGRs.

Prof. Dr. DG Webster and Associate Prof. Dr. Leandra Goncalves co-lead the Taskforce on Ocean Governance, a new collaboration of researchers on marine issues within the Earth System Governance Community. Their research focus lies on the institutional design of the BBNJ agreement, pointing to the threat of creating “panaceas” out of well-intentioned provisions. Some issues can be interpreted differently among actors, which on the one hand is an opportunity for compromise, but on the other hand guards the threat of leading to ineffective governance. This can be seen in the case of establishing ABMTs in areas of little economic activity to enhance political willingness and implementation. Prof. Webster cautions that some actors might be interested in ambiguous language to prevent specific rules and regulations and continue to use the ocean’s resources as the status quo currently allows the exploitation of MGRs without further details in regulation. Assoc. Prof. Goncalves focuses on the case of Brazil and political, economic intentions behind its foreign policy within the BBNJ negotiations. She is observing the role of Brazil and the influence of the current government within the negotiations and regional groups, namely the Core Latin American Countries (CLAM) and the Group of 77 and China.

Providing Capacity for Implementation

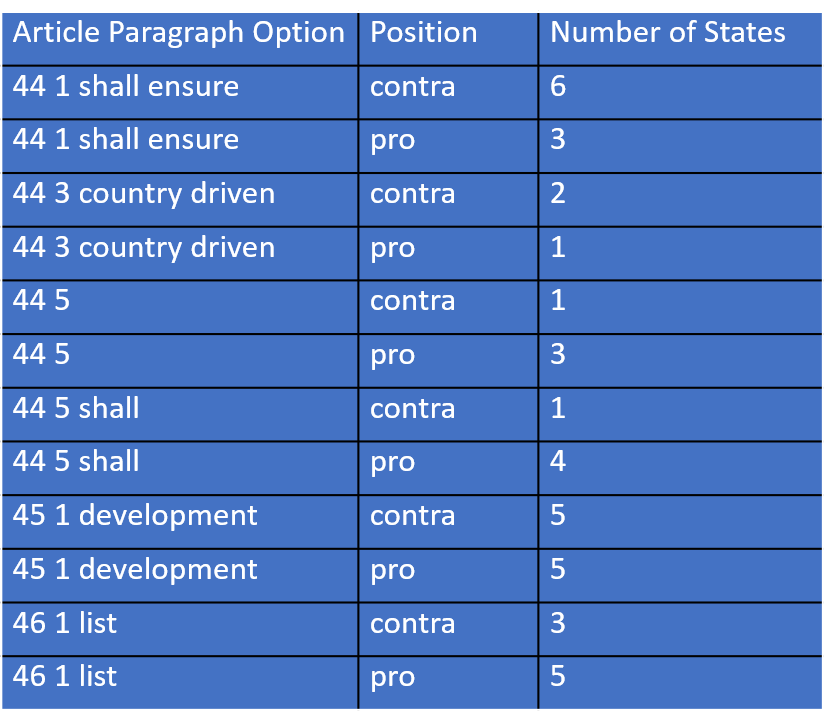

Ensuring that all states have the capacity to implement the BBNJ agreement requires capacity building and the transfer of marine technology (CB&TT). Dr. Harriet Harden-Davies, Nippon Foundation Ocean Nexus postdoctoral research fellow at the Australian National Centre for Ocean Resources and Security at the University of Wollongong, focuses her research on Capacity building and Technology Transfer concerning the BBNJ agreement.

While UNCLOS lays out regulations for the transfer of marine technology, technical capacities for conducting ocean science are still unequally shared among countries and regions. Capacity building and technology transfer includes access to data, training courses, time at sea, research cruise and cooperation. While these are in general very useful initiatives, however, Harriet stresses that they do not work well as a “one way donation”. Harriet emphasises the need for genuine, collaborative two-way partnerships, designed to meet the needs for ocean-dependent people from the start. Within the BBNJ draft, she applauds the envisaged multi-way partnerships and the references to needs assessments, meeting self-determined priorities of ocean-dependent states (Art. 44 and 46). She also highlights the importance of the Clearing House Mechanism (Art. 51), Funding (Art. 52) and Monitoring and Evaluating the long-term outcomes of capacity building, instead of individual outputs.

What is the State of the BBNJ negotiations? – Where are we now?

With more than 2 years of intersessional period, there has been some progress in the negotiations on a number of issues, thanks to the online discussions, online webinars and workshops and bilateral and multilateral meetings on national, regional and international levels.

Despite progress on some issues, many are still unresolved that will need to be discussed – ideally before the final round of negotiations in New York next March. With experts from governmental, former UN agencies and non-governmental actors, who have been actively involved in the political discussions since the early beginnings of the BBNJ negotiations, the panel identified main areas of divergence in the negotiations that yet need to be resolved.

Despite progress on some issues, many are still unresolved that will need to be discussed – ideally before the final round of negotiations in New York next March. With experts from governmental, former UN agencies and non-governmental actors, who have been actively involved in the political discussions since the early beginnings of the BBNJ negotiations, the panel identified main areas of divergence in the negotiations that yet need to be resolved.

We invited Gabriele Goettsche-Wanli, former Director of the Division for Ocean Affairs and the Law of the Sea, Office of Legal Affairs and Sophie Mirgaux, Belgium’s Special Envoy for the Ocean, who are both actively involved in moderating and organising the High Seas Treaty Dialogues, an important informal exchange between BBNJ stakeholders in the intersessional period. Moreover, we invited Kahlil Hassanali, a negotiator in the BBNJ negotiations for the regional group Caribbean Community (CARICOM) and Julian Jackson, a non-state actor, representing The Pew Charitable Trusts in the BBNJ process.

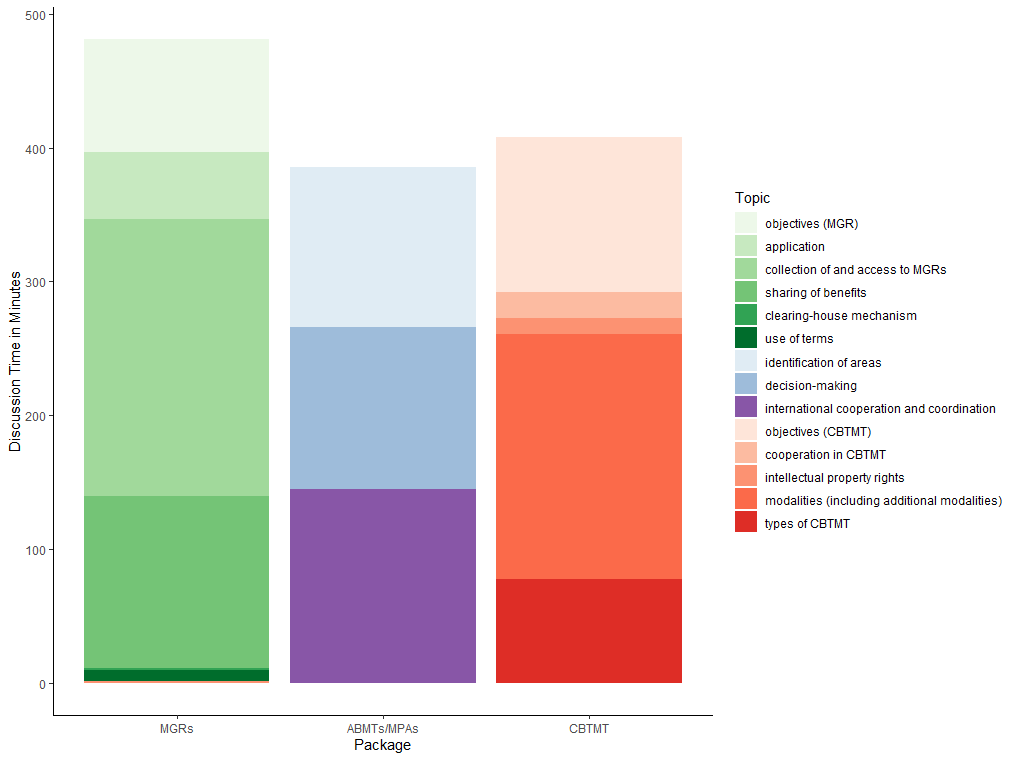

Using and Sharing the Riches of the Ocean

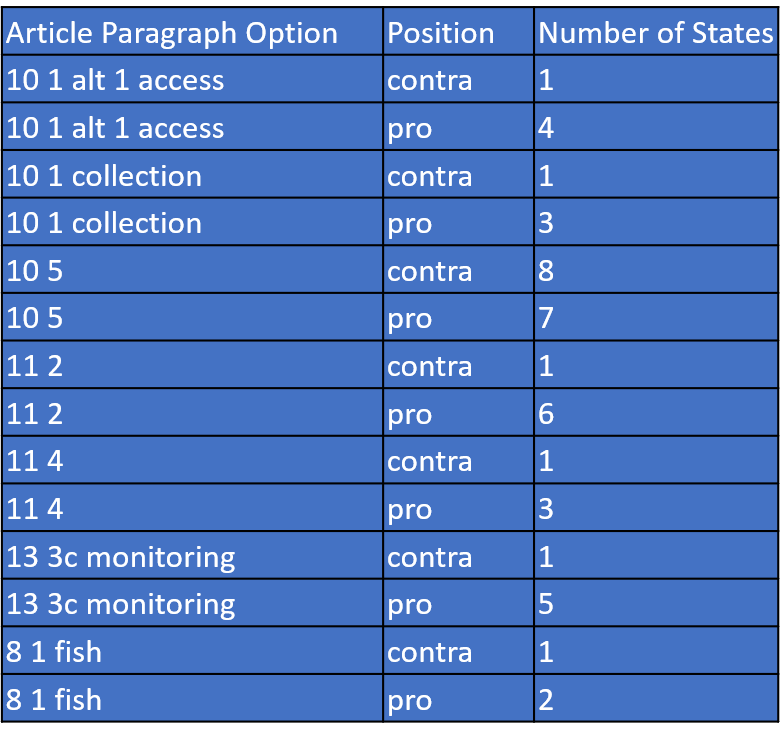

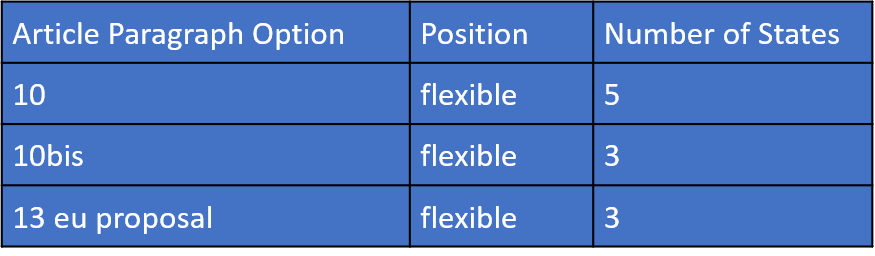

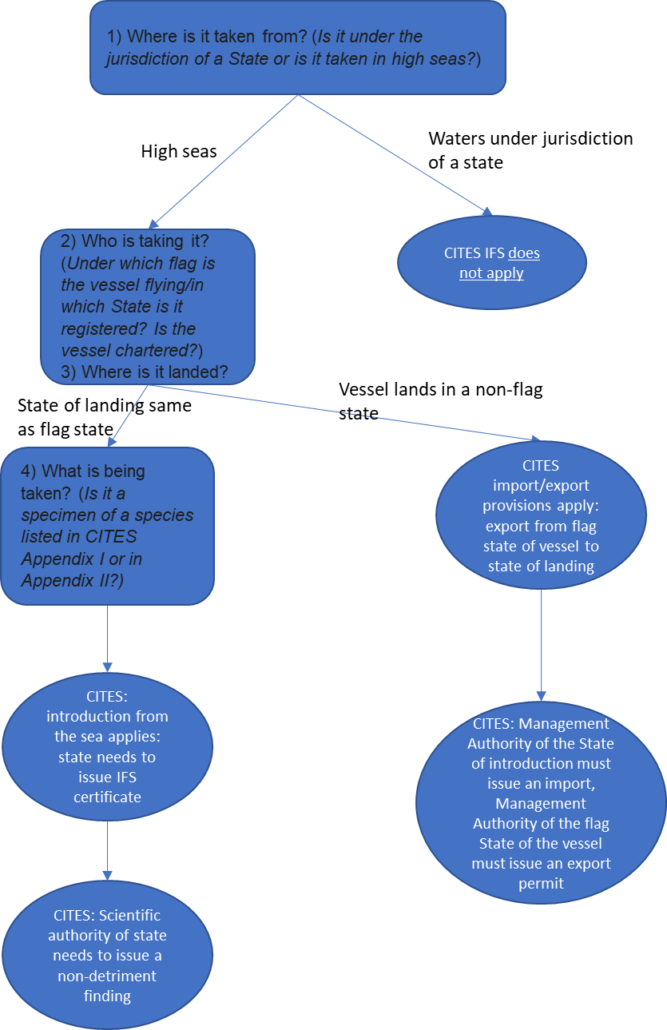

If you are new to the negotiations and you are looking at the outstanding issues of the package element of marine genetic resources (MGRs), you might wonder whether this topic has not been included so far in discussions. We asked Gabriele Goettsche-Wanli, former Director of the Division for Ocean Affairs and the Law of the Sea, Office of Legal Affairs, to summarise outstanding issues of this package element. The very key questions of whether, if so how, when and by whom, benefits from MGRs will be shared and whether this will be voluntary or mandatory are not yet agreed upon. This is largely due to the long entrenched conflict between the supporters of the principle of common heritage of humankind, and the proponents of the principle of the High Seas for the governance of MGRs in areas beyond national jurisdiction (ABNJ) (Vadrot et al., 2021).

The discussion whether benefits from MGRs that originate from areas beyond national jurisdiction have been present since the very beginnings of the negotiations and are to date not resolved (Vadrot et al., 2021). Global commons are resources that do not belong to anyone, but need to be jointly shared and protected, while at the same time, UNCLOS sets out general rights and obligations for activities on the High Seas. In this regard, there are opposing views whether MGRs should fall under the Common Heritage of Humankind or the Freedom of the High Seas Principle.

The discussion whether benefits from MGRs that originate from areas beyond national jurisdiction have been present since the very beginnings of the negotiations and are to date not resolved (Vadrot et al., 2021). Global commons are resources that do not belong to anyone, but need to be jointly shared and protected, while at the same time, UNCLOS sets out general rights and obligations for activities on the High Seas. In this regard, there are opposing views whether MGRs should fall under the Common Heritage of Humankind or the Freedom of the High Seas Principle.

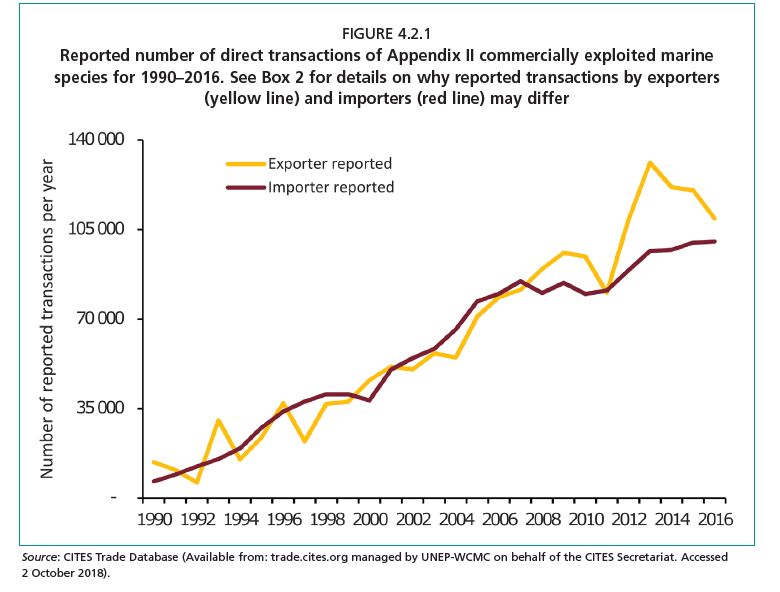

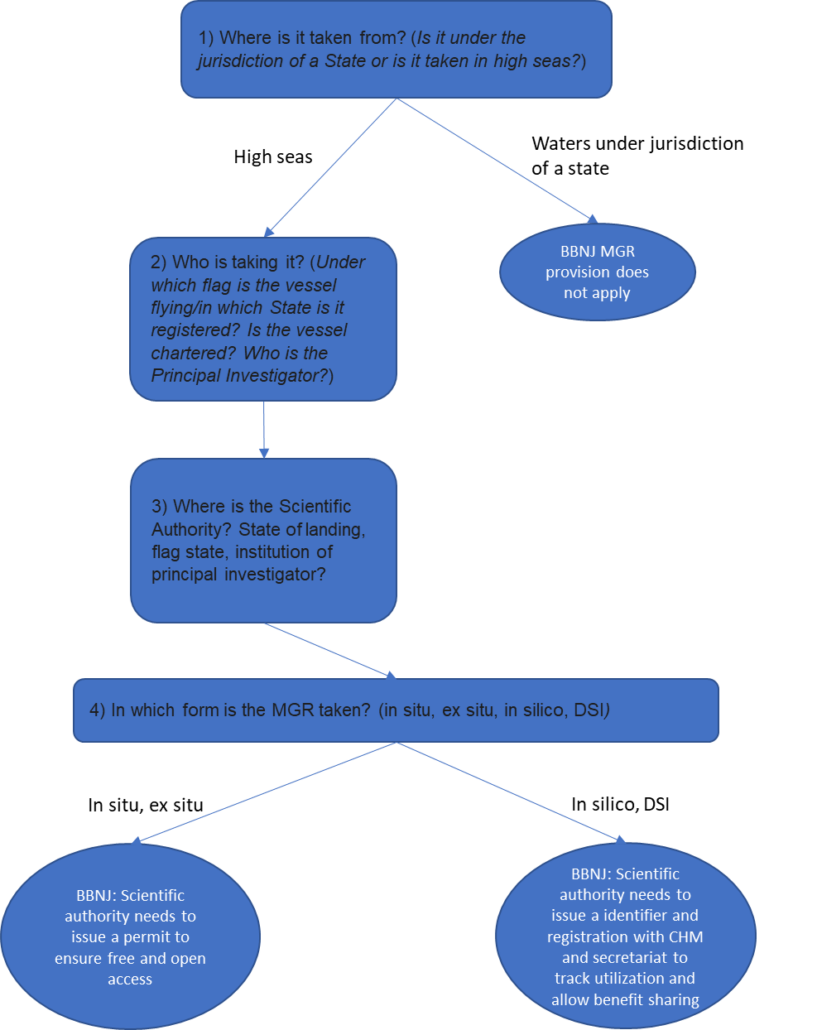

Further contentious points regard what will ultimately fall under MGRs – will this be only marine genetic material that is found in the ocean (in situ), or does it also include samples stored elsewhere in collections (ex situ), and data on these resources in digital form and their genetic sequences (digital sequence information – DSI) and derivatives?

Regarding traditional knowledge of Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities, the discussions are still ongoing how this knowledge can be accessed, if at all – will it need to be based on the free, prior and informed consent of the traditional knowledge holders and how will it be shared ethically if the traditions of passing on knowledge are inherently different to our technological ways of sharing data online?

Open questions also regard how the agreement will trace MGRs (Humphries et al., 2021) and whether and if so how intellectual property rights be addressed in the new agreement.

Limiting Exploitation of the Ocean

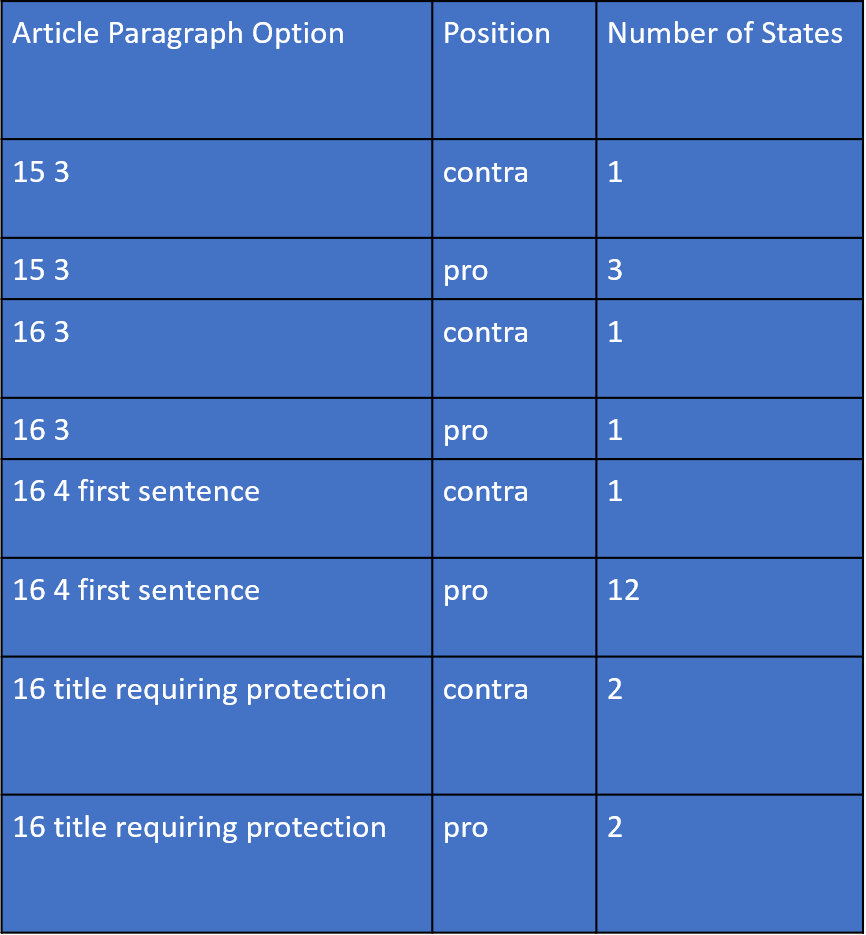

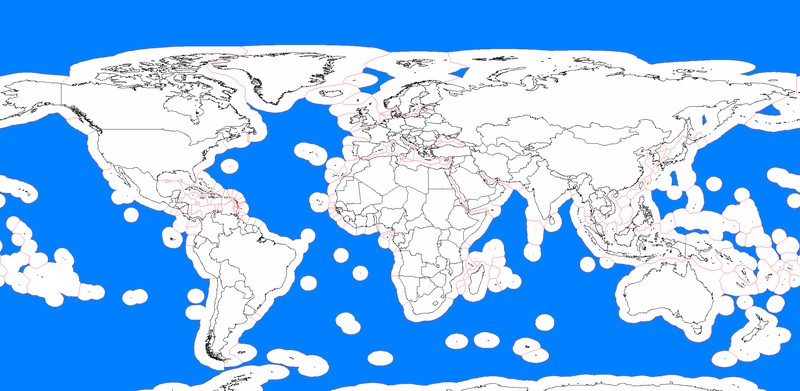

The panel also talked about the package element of Area-Based Management Tools (ABMTs), including Marine Protected Areas (MPAs). This provision seeks to protect certain areas from (unsustainable) human activities. There is already a patchwork of biodiversity governance existent with mandates to establish areas for conservation and sustainable use in different geographical regions and issue areas[4].

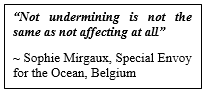

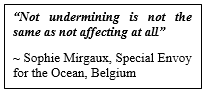

Therefore, political discussions often include a divergence of views on the relationship between the new BBNJ agreement and already existing instruments, bodies and frameworks that are governing marine biodiversity under specific regional and sectoral mandates. Fear of duplication and competition of mandates triggers arguments to “not undermine” existing efforts (Ardron et al., 2014; Friedman, 2019; Scanlon, 2018). In light of the connection of the ocean, it is evident that an effective conservation and sustainable use of marine biodiversity requires synergies to existing agreements. What state representatives in BBNJ exactly understand under “not undermining” is an ongoing discussion. Sophie Mirgaux, Special Envoy for the Ocean for the Belgian Ministry of Environment, clarifies that existing frameworks will not be wiped away by the BBNJ agreement, but that the new agreement can indeed have an effect on the existing:

She quotes Dire Tladi (Professor of International Law and SARChI Chair in International Constitutional Law at the University of Pretoria) in explaining that it is a basic rule in international law that states can adhere to more stringent rules in new agreements, which does not mean they are undermining another agreement they have signed in the past.

She quotes Dire Tladi (Professor of International Law and SARChI Chair in International Constitutional Law at the University of Pretoria) in explaining that it is a basic rule in international law that states can adhere to more stringent rules in new agreements, which does not mean they are undermining another agreement they have signed in the past.

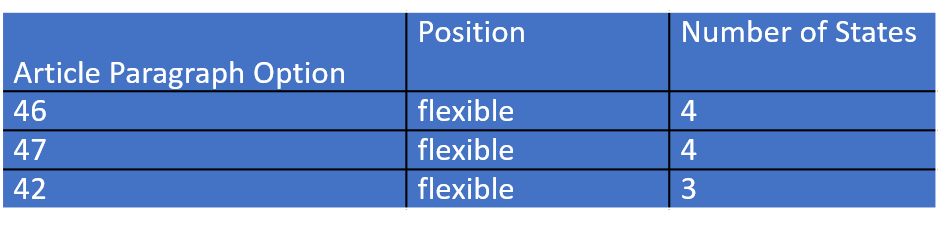

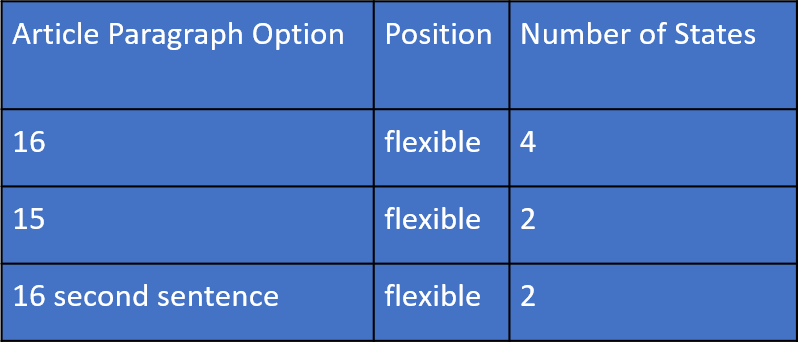

During the BBNJ negotiations, it is yet to be determined what role the Conference of the Parties (COP) will play – whether it should make recommendations, or ultimately decide on the establishment of ABMTs, including MPAs, and their management plans. Another outstanding question concerns the decision-making procedures. She cautions against taking decisions exclusively by consensus, as this bears the risk for inaction.

Living sustainably with the Sea

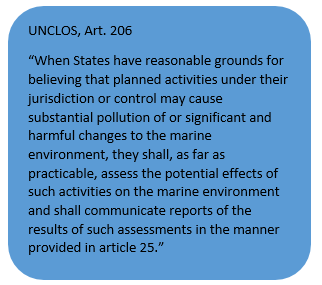

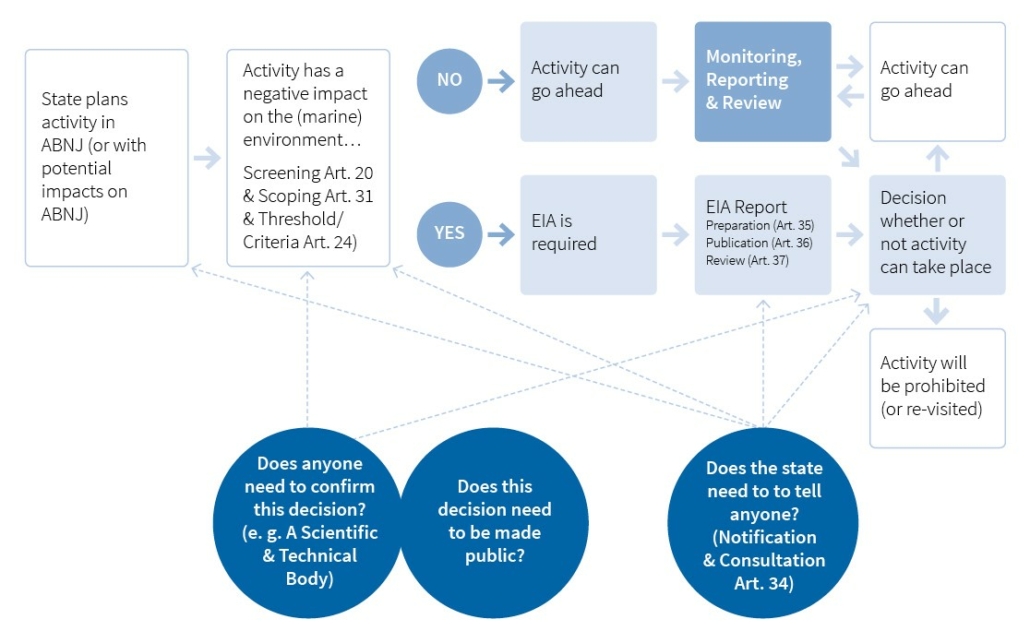

Another part of the new agreement regards Environmental Impact Assessments (EIAs) in areas beyond national jurisdiction. How will states agree to live sustainably alongside biodiversity without leaving a footprint that stays forever? In the package element regarding EIAs, there are still many issues to be agreed upon by BBNJ negotiators. Kahlil Hassanali, lead coordinator for EIAs for the Caribbean Community negotiating bloc (CARICOM), identifies three major unresolved areas that will determine the effectiveness of the EIA process in ABNJ in the future:

Firstly, the degree to which the BBNJ agreement will be internationalised has not been agreed on. This regards the question how to ensure genuine participation of all stakeholders, including marginalised or affected groups, as well as interested public. Moreover, internationalisation also concerns the discussion whether there should be global oversight over decision-making. This is particularly relevant as areas beyond national jurisdiction are a global common. He asserts that some developed countries would like to see this process to be “state-led”, meaning that the states proposing activities would be the ones ultimately deciding on whether the activity can take place. In light of the fact that the ocean is a global common and developing countries simply do not have the same capacities as developed countries to undertake activities in international waters, he suggests to introduce some sort of global oversight to ensure inclusive decision-making to permit activities.

Secondly, it is still unclear whether activities that are undertaken exclusively in ABNJ or whether all activities with an impact on ABNJ would be considered for the BBNJ EIA process. This discussion is delicate as states have certain rights within their territorial waters and exclusive economic zones.

Thirdly, questions remain on how the BBNJ agreement will interact with other existing processes (See not undermining discussion in previous section).

Sharing Knowledge with the World

There are global controversies regarding capacity constraints and uneven capacities to undertake research, including to access MGRs, designate and monitor ABMTs, including MPAs and to evaluate EIAs. The package element of Capacity Building and Transfer of Marine Technology (CB&TT) seeks to address this challenge; however, there are various outstanding issues still to be resolved.

Key issues concern the questions whether capacity building will be only voluntary or additionally  include a mandatory component, who would benefit from CB&TT and whether it would be provided on mutually agreed terms and the inclusion of different types of CB&TT.

include a mandatory component, who would benefit from CB&TT and whether it would be provided on mutually agreed terms and the inclusion of different types of CB&TT.

How to identify the needs of parties and who to benefit and what kind of CB&TT would be required. This triggers the question of whether there should be a list of CB&TT, the possibility of a potential CB&TT committee and whether a financial mechanism could provide funding covering CB&TT issues.

Further outstanding issues regard how the package element of CB&TT relates to cross-cutting issues, for instance, the clearing house mechanism. How would this data-sharing platform most effectively support the CB&TT package element?

The Devil in the Detail

It is yet to be seen if the BBNJ agreement will be ambitious. What this essentially means is: Now is the drafting stage of the agreement, what goes into the agreement now, will be carved into the marvel of international law. Not to say, that this will be set in stone, but it will set the guidance for how humans will govern areas of the ocean that are so far away from our shores where one may not feel connected to this part of the planet but in reality, is the soul of our existence.

Civil society actors are involved in the BBNJ negotiations, represented through a number of different NGOs, including The PEW Charitable Trusts. They have an important role in strengthening transparency and accountability of the process. By observing the discussion, they can provide information for other NGOs that are not able to attend, which is done through their publications, as well as the High Seas Alliance Treaty Tracker. In this way, momentum can be kept among negotiators and in society; and political pressure be built. Civil society organisations also take part in actively supporting the process through capacity building in form of providing basic background for newly joining delegates in the BBNJ process.

Julian Jackson explains the important details of the agreement that need to be understood and closely considered to ensure an ambitious treaty for the ocean: For an ambitious treaty, the precautionary approach and a robust mechanism for environmental impact assessments are important for The PEW Charitable Trusts.

He points to the possibility of exclusions in international law, meaning that states can identify different parts of the agreement, to which they would not need to adhere to, inherently decreasing the ambition and potentially also the effectiveness of the agreement. He emphasises the importance of no exclusions. He is particularly concerned about the discussion among negotiators to exclude fish from the agreement. This is closely connected to the “not undermining” discussion, and would mean that fish would not be regarded as marine biodiversity to be conserved and sustainably used. He stresses the need for the BBNJ agreement to complement Regional Fisheries Management Organisations, but also the relationship to other issues related to marine biodiversity, such as shipping and deep-sea mining.

He points to the possibility of exclusions in international law, meaning that states can identify different parts of the agreement, to which they would not need to adhere to, inherently decreasing the ambition and potentially also the effectiveness of the agreement. He emphasises the importance of no exclusions. He is particularly concerned about the discussion among negotiators to exclude fish from the agreement. This is closely connected to the “not undermining” discussion, and would mean that fish would not be regarded as marine biodiversity to be conserved and sustainably used. He stresses the need for the BBNJ agreement to complement Regional Fisheries Management Organisations, but also the relationship to other issues related to marine biodiversity, such as shipping and deep-sea mining.

Another unresolved issue is under which condition the agreement should enter into force. There are several options of how this could look like, e.g. certain number of signatories. However, it is important to balance between an early entry into force vs. a larger number of signatories (up to universality of the agreement). While it is necessary to have a legally binding agreement on this issue as soon as possible, it also needs to have a meaningful number of parties as signatories.

Identified main areas of divergence in the negotiations also include compliance and dispute settlement and the role of the clearing house mechanism for each of the package elements. There is also an ongoing concern of non-parties to UNCLOS about their status in the BBNJ agreement that would have to be solved.

How can Research contribute to the BBNJ process?

The BBNJ process has contributed from research by multiple fields and continues to be informed by new knowledge. Political momentum and targets can be created on the basis of scientific findings, such as in the case of the 30×30 campaign which aims to protect 30% of the Ocean by 2030[5]. Practitioners emphasised the importance of science for the BBNJ negotiations, throughout the BBNJ process and beyond. If you are a scientist working on or planning to work on marine biodiversity, here are some ideas from the practitioners that would be needed in the BBNJ process:

The BBNJ process has contributed from research by multiple fields and continues to be informed by new knowledge. Political momentum and targets can be created on the basis of scientific findings, such as in the case of the 30×30 campaign which aims to protect 30% of the Ocean by 2030[5]. Practitioners emphasised the importance of science for the BBNJ negotiations, throughout the BBNJ process and beyond. If you are a scientist working on or planning to work on marine biodiversity, here are some ideas from the practitioners that would be needed in the BBNJ process:

Social Science

- Integration of traditional knowledge of indigenous Peoples and Local Communities (and other forms) into the different BBNJ package elements

- (Under-) representation of stakeholder groups in the BBNJ process, how they can engage and their voices be heard

- Role of Coastal States; marginalised groups, indigenous Peoples and Local Communities

Natural Science:

- Climate change science (Climate- Ocean Nexus)

- Research on mesopelagic fish and impact on carbon cycle

- Biological research

- Recent scientific development of handling samples (of MGRs)

- Information on scientific practices concerning the access and use of MGRs

- Scientific capacities and needs in different regions

Social & Natural Science:

- Connection between ABNJ and Coastal Waters: effects on a) (marine) ecosystems; b) coastal states and other actors

- Science-policy interfaces and how can they be improved

- Research on human-ocean relationship

- Effective management measures for MPAs

- Research on the technical side: monitoring, control and surveillance options (e.g. non-human drones)

Sometimes, getting the information the policy-makers seems to be a hindrance, with a myriad of information out there. Science-policy interactions, such as organised meetings among scientists and policy-makers are valuable instances of exchange and mutual learning. Sophie Mirgaux emphasised the openness of the Belgium government and the EU to new scientific findings and encouraged scientists working on these issues that have not had direct contact with policy-makers to contact the ministries directly. These will forward requests to the responsible department. Participant lists are available for the BBNJ negotiations (and other negotiations) where names of state delegates can be found to direct the email to. Julian Jackson stressed the importance for scientists to inspire others and “get people excited about the deep sea”.

What can you do?

You are a scientist? Explain and communicate your research to policy-makers and society; reach out online/on site at conferences; show why your research matters to you; talk to other scientists; participate in panels and meetings and workshops.

You are a policy-maker? Take time to understand the relevance of research in your issue area (for you and others); identify links to other agreements; be open to innovative thoughts from scientific communities; participate in panels, meetings and workshops; think outside of the box.

You are a world citizen? Be interested and informed about what is happening in BBNJ; use the High Seas Alliance Treaty Tracker; Earth Negotiation Bulletin; get involved.

You are all of the above? Bring them together; share your knowledge; engage.

Overwhelmed?

Take the first step into unknown waters…

Helpful information links on BBNJ:

United Nations Website on BBNJ; – Formal Website with all documents and dates

BBNJ Informal Intersessional Dialogues (High Seas Treaty Dialogues) Informal Exchanges in Intersessional Period

MARIPOLDATA BBNJ Governance Database; Overview of the Science on BBNJ Governance

MARIPOLDATA Country Dashboard; Information on Actors and Topics in BBNJ

MARIPOLDATA Ocean Seminars; Monthly discussions with experts on Ocean Science and Governance

High Seas Alliance Treaty Tracker; Summaries and Analyses of Positions in BBNJ

Earth Negotiation Bulletin; Daily BBNJ News during Conferences

Newsletters/ Events:

MARIPOLDATA

DOSI

IDDRI

References

Ardron, J. A., Rayfuse, R., Gjerde, K., & Warner, R. (2014). The sustainable use and conservation of biodiversity in ABNJ: What can be achieved using existing international agreements? Marine Policy, 49, 98-108. doi:10.1016/j.marpol.2014.02.011

Barros-Platiau, A.F., Søndergaard, N., & Prantl, J. (2019). Policy networks in global environmental governance: connecting the Blue Amazon to Antarctica and the Biodiversity Beyond National Jurisdiction (BBNJ) agendas. Revista Brasileira de Política Internacional, 62. Retrieved from http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0034-73292019000200206&nrm=iso

Blasiak, R., Pittman, J., Yagi, N., & Sugino, H. (2016). Negotiating the Use of Biodiversity in Marine Areas beyond National Jurisdiction. Frontiers in Marine Science, 3. doi:10.3389/fmars.2016.00224

Clark, N.A. (2020). Institutional arrangements for the new BBNJ agreement: Moving beyond global, regional, and hybrid. Marine Policy, 104143. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2020.104143

De Santo, Ásgeirsdóttir, Á., Barros-Platiau, A., Biermann, F., Dryzek, J., Gonçalves, L.R., . . . Young, O. (2019). Protecting biodiversity in areas beyond national jurisdiction: An earth system governance perspective. Earth System Governance, 2, 100029. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esg.2019.100029

Friedman, A. (2019). Beyond “not undermining”: possibilities for global cooperation to improve environmental protection in areas beyond national jurisdiction. ICES Journal of Marine Science, 76(2), 452-456. doi:10.1093/icesjms/fsy192

Gjerde, K., Clark, N., & Harden-Davies, H. (2019). Building a Platform for the Future: the Relationship of the Expected New Agreement for Marine Biodiversity in Areas beyond National Jurisdiction and the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea. Ocean Yearbook, 33, 1-44. doi:10.1163/9789004395633_002

Hassanali, K. (2021). Internationalization of EIA in a new marine biodiversity agreement under the Law of the Sea Convention: A proposal for a tiered approach to review and decision-making. Environmental Impact Assessment Review, 87, 106554. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eiar.2021.106554

Humphries, F., & Harden-Davies, H. (2020). Practical policy solutions for the final stage of BBNJ treaty negotiations. Marine Policy, 104214. doi:10.1016/j.marpol.2020.104214

Humphries, F., Rabone, M., & Jaspars, M. (2021). Traceability Approaches for Marine Genetic Resources Under the Proposed Ocean (BBNJ) Treaty. Frontiers in Marine Science, 8, 430. Retrieved from https://www.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fmars.2021.661313

Mossop, J. (2018). The relationship between the continental shelf regime and a new international instrument for protecting marine biodiversity in areas beyond national jurisdiction. ICES Journal of Marine Science, 75, 450. doi:10.1093/icesjms/fsx111

Orejas, C., Kenchington, E., Rice, J., Kazanidis, G., Palialexis, A., Johnson, D., . . . Roberts, J. M. (2020). Towards a common approach to the assessment of the environmental status of deep-sea ecosystems in areas beyond national jurisdiction. Marine Policy, 121, 104182. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2020.104182

Payne, C. (2020). Negotiation and Dispute Prevention in Global Cooperative Institutions: International Community Interests, IUU Fishing, and the Biodiversity Beyond National Jurisdiction Negotiation. International Community Law Review, 22(3-4), 428-438. doi:https://doi.org/10.1163/18719732-12341439

Scanlon, Z. (2018). The art of “not undermining”: possibilities within existing architecture to improve environmental protections in areas beyond national jurisdiction. ICES Journal of Marine Science, 75(1), 405-416. doi:10.1093/icesjms/fsx209

Spooner P., Thornalley D., Cunningham S., & Roberts J.M. (2020). ATLAS Policy Brief – Changing Ocean State and its Impact on Natural Capital. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3946683

Tessnow-von Wysocki, I., & Vadrot, A.B.M. (2020). The Voice of Science on Marine Biodiversity Negotiations: A Systematic Literature Review. Frontiers in Marine Science, 7(1044). doi:10.3389/fmars.2020.614282

Warner, R. (2018). Oceans in transition: Incorporating climate-change impacts into environmental impact assessment for marine areas beyond national jurisdiction. Ecology Law Quarterly, 45, 31-51. doi:10.15779/Z38M61BQ0J

Wright, G., & Rochette, J. (2017). Regional Management of Areas beyond National Jurisdiction in the Western Indian Ocean: State of Play and Possible Ways Forward. The International Journal of Marine and Coastal Law, 32(4), 765-796. doi:https://doi.org/10.1163/15718085-13204020

Vadrot, A. B. M., Langlet, A., & Tessnow-von Wysocki, I. (2021). Who owns marine biodiversity? Contesting the world order through the ‘common heritage of humankind’ principle. Environmental Politics, 1-25. doi:10.1080/09644016.2021.1911442

[1] More information on the Virtual Intersessional Work: https://www.un.org/bbnj/content/Intersessional-work

[2] More information on these Informal Intersessional Dialogues: https://highseasdialogues.org/

[3] Information on the iAtlantic Fellow Scheme: https://www.atlanticfellows.org/

[4] See Figure in Tessnow-von Wysocki & Vadrot, 2020: https://www.frontiersin.org/files/Articles/614282/fmars-07-614282-HTML/image_m/fmars-07-614282-g001.jpg

[5] 30 x 30 initiative, See more information: https://www.oceanunite.org/30-x-30/

This contribution is part of a MARIPOLDATA blog series on current developments and discussions about the negotiations towards an

This contribution is part of a MARIPOLDATA blog series on current developments and discussions about the negotiations towards an

By: Elisa Morgera, Bernadette Snow and Mia Strand, One Ocean Hub; Alice Vadrot, Arne Langlet and Silvia Ruiz Rodríguez, University of Vienna, ERC Project MARIPOLDATA

By: Elisa Morgera, Bernadette Snow and Mia Strand, One Ocean Hub; Alice Vadrot, Arne Langlet and Silvia Ruiz Rodríguez, University of Vienna, ERC Project MARIPOLDATA